A Road Less Travelled – Brexit and the UK’s trade policy

The UK has stated its intention to prioritise “friction-free” trade in goods with the EU, whilst also planning to implement its own trade policy with the rest of the world meaning withdrawal from the EU’s Common Commercial Policy and the Customs Union on goods. Meanwhile, the EU has said that there can be no cherry-picking of aspects of the single market. Amar Breckenridge of Frontier Economics discusses UK trade policy issues as UK-EU phase 2 begins.

8th January 2018

The journey so far

Following its decision to invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, the UK government entered into negotiations with the European Union on the terms of the UK’s withdrawal from the Union. Under the guidelines agreed for the negotiations, sufficient progress was required on three issues – the rights of existing EU citizens, the question of the Irish border, and the financial settlement payable by the UK – as a precondition for talks on future arrangements. On 15 December, the European Council agreed that sufficient progress had been made on these three issues, giving the green light for phase 2 of the talks.

The European Union has suggested that formal talks on trade and related policies will not begin before March 2018. In reality, positioning for the talks has been underway for a while. The UK government had, early in 2017, set out as it overarching ambition the negotiation of a “deep and comprehensive” free trade agreement. The UK government then subsequently requested a two-year transition period bridging current and future arrangements,

The UK government also stated its intention to keep trade with the EU as “friction free” as possible. This means, in addition to avoiding customs duties, avoiding as much as possible administrative and compliance costs related to formalities at the border. Finally, as made clear through both the Trade Bill and Customs Bill, the UK aims to implement its own trade policy vis a vis the wider world, which would mean withdrawing from the EU’s Common Commercial Policy, and the Customs Union on goods.

The EU for its part has set out certain broad parameters. Any transition period will require continued implementation of EU rules, including the common commercial policy; and there can be no cherry-picking of aspects of the single market.

Signposts along the way

There are some 280 free trade agreements currently in force and that have been notified to the WTO. But the negotiations between the UK and the EU are very different to others. That is because most free trade negotiations involve partners seeking to deepen levels of mutual liberalisation, usually working off WTO commitments as a baseline. In this case, the negotiation involves two partners seeking to redefine, and probably reduce, their levels of policy integration. Moreover, the degree of internal liberalisation within the EU, and to which the UK has been a major contributor and beneficiary, is without parallel in other trade agreements.

Within this context, what pointers can guide these negotiations?

The UK is correct to prioritise “friction-free” trade in goods with the EU.

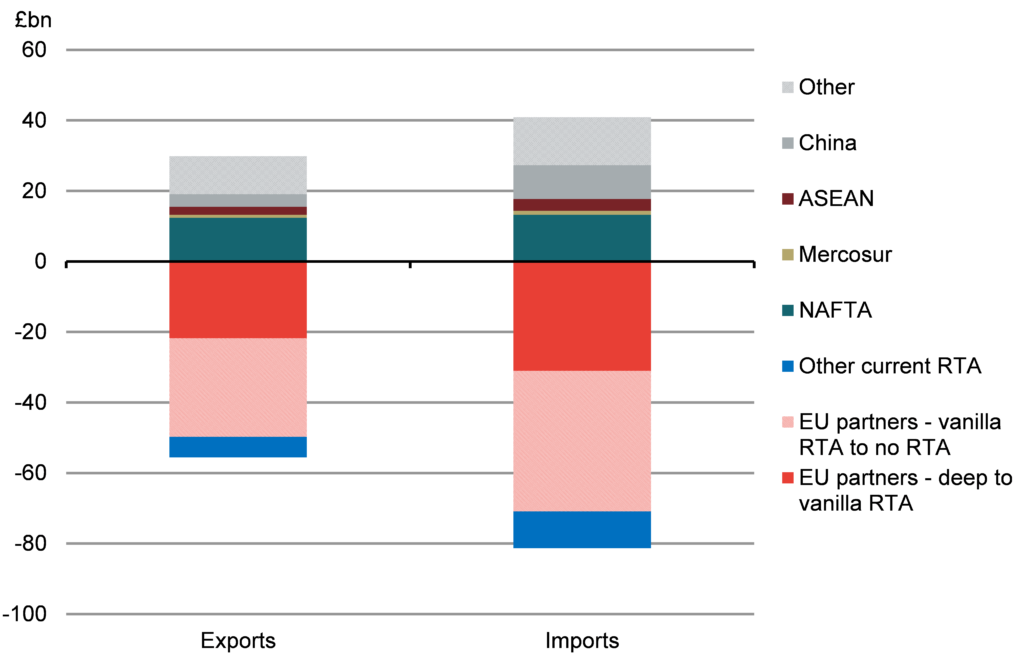

Using a gravity model of trade, we estimate the effects on UK exports of moving from its current level of integration to either a generic free trade agreement, resembling those in force outside the EU, or to trade on Most-Favoured Nation terms. The results are depicted in the bottom section of figure 1. The red-shaded part depicts losses if the UK were to move to a generic free trade agreement; the red and hatched parts depict the losses from moving to MFN terms. The extra blue section shows further losses associated with the UK falling out of FTAs the EU negotiated with the rest of the world.

The top section gives gains to the UK from concluding and implementing FTAs with major non-EU trade partners. A key result is that even if the UK were to sign agreements with all major trading partners, it could not offset the losses incurred from leaving the EU. Note that even this assumes, completely unrealistically, that agreements between the UK and major non-EU partners could be negotiated and fully implemented by the point of Brexit.

The devil really is in the detail

The results at first blush suggest that if the UK and the EU were to conclude a generic trade deal, and the UK signed agreements with the rest of the world, there is a chance the UK would not be left worse off relative to its current position. Moreover, the deeper the agreement (i.e. the smaller the total area below the line) the fewer the agreements it might need to sign.

But this path is beset by various perils. That is because the modelling glosses over a deep-seated tension between two objectives: namely to minimise losses on trade with the EU, on one hand, and to maximise trade with other countries to compensate, on the other. This tension has to do in the first instance with the question of rules of origin.

If the UK leaves the customs union, but agrees some sort of FTA with the EU, it will need to agree rules of origin with the EU.[1] These will be required, for example, to avoid goods leaking into the EU from third countries that have signed a FTA with UK but do not have one with the EU.

Such rules will likely impose an entirely new set of costs on UK and EU firms that depend on cross-border supply chains that span the UK and EU. The UK’s supply chains are deeply integrated with the rest of the EU. OECD data suggest that at present, most (80-90%) of foreign value-added in UK final demand and exports comes from the EU. Preserving “friction-free” access to the EU’s single market is essential to the protection of the competitive position of many UK (and EU) businesses.

This tension explains the Government’s position, announced in its August position paper on Customs Arrangements, to seek arrangements on rule of origin that mirror the EU’s arrangements with third parties, with the intention of eliminating additional compliance costs on UK-EU supply chains. The mechanics are not spelled out, and need careful thought to avoid creating the sort of administrative labyrinth the Government wants to avoid.

Moreover, if the UK commits to mirroring the EU’s customs arrangements with non-EU partners, this could constrain the amount of preferential liberalisation the UK could offer these partners through a FTA, and they in return. Put crudely, reducing the area “below the line” in Figure 1 is likely to become more difficult the more gains above the line are pursued.

Finally, the challenges surrounding rules of origin generalise to “behind-the-border” issues that affect trade, such as regulatory issues (for example, food safety requirements). Demonstrating equivalence is likely to add to administrative costs, a problem that is also likely to affect services.

What’s on offer for services?

Services account for 80% of the UK’s trade. They are the fastest growing part of world trade. So if options are constrained on goods for reasons described, what agenda could the UK pursue on services?

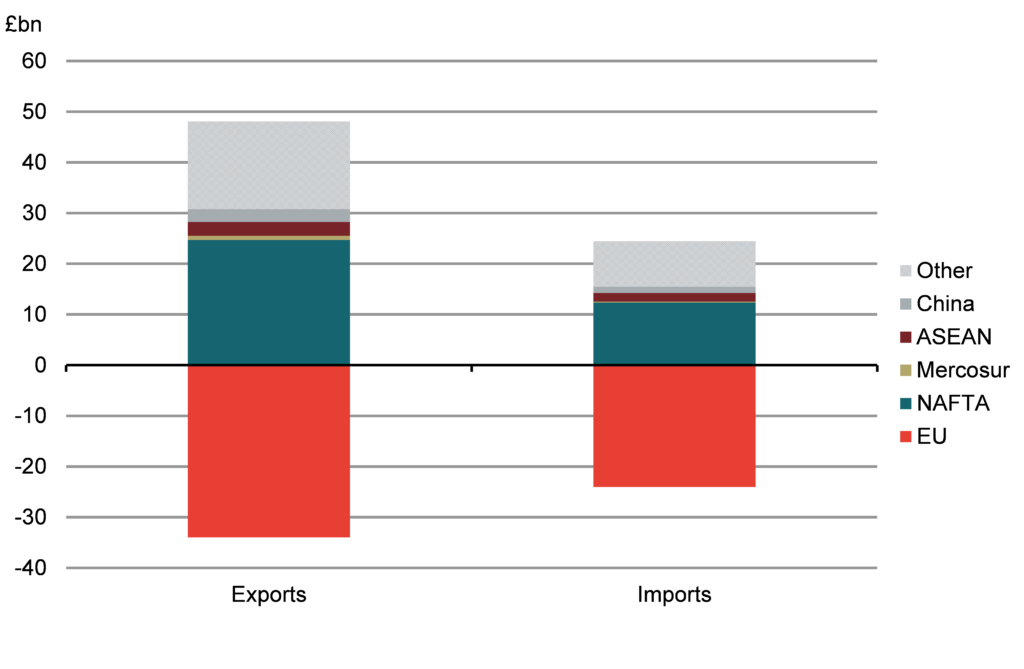

In figure 2 we present modelling results for services trade scenarios vis a vis the EU and the rest of the world. The area in red depicts the value at risk from rolling back UK services’ access to the EU single market and reverting to trade on MFN terms. Exports would fall by around £34 billion per year and imports by around £24 billion.

Could these losses be offset by FTAs with the rest of the world? If the UK were to sign services FTAs with the rest of the world it could more than compensate for losses on its EU-facing services trade. An agreement with NAFTA economies would, for example, increase services exports by around £24 billion per year.

If the UK could retain some level of preferential free trade with the EU so that it reduces its losses (i.e. shrinks the red area), then it could conceivably break-even. For example, it might be able to negotiate an equivalence agreement with the EU on financial services, allowing UK based institutions continued access to an EU passport, and thus the ability to trade seamlessly across EU-borders.

But these results need to be treated with caution. First, in order to generate the sorts of gains with partners such as the US, the UK would need to negotiate an agreement that achieves similar levels of internal liberalisation as within the EU. These have taken decades to achieve. Moreover, there are close linkages between services liberalisation and the free movement of labour. Such a scale of liberalisation would be unprecedented outside the EU: services liberalisation in free trade agreements has generally been minimal, even within so-called “next- generation” agreements such as the one between Canada and the EU.

Moreover, one of the key questions in services is regulation. Approaches to regulation differ markedly between jurisdictions, and notably between the EU and the US. This is one reason why progress on the EU-US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership was nigh impossible to achieve.

The UK’s existing FTAs – not just cut and paste

The UK is currently party to a number of FTAs with the rest of the world via its membership of the EU’s common commercial policy. Once it leave the EU, it will drop out of these agreements. The default assumption is that the UK and these partners could simply roll over these agreements – a trade policy cut and paste job – before turning to future negotiations that may deepen them

But this may be presumptuous. For trade partners, the attractiveness of a trade agreement with the UK is different to one with the UK as one of 27 EU members. For example, a Canadian firm could have used the UK has a point of entry to access or develop pan-EU value chains. This prospect is diminished by a UK outside the EU. Hence, the partner may seek a range of other commitments as “payment”, to use a mercantilist expression, for liberalisation offered to the UK.

A sort of homecoming

The results presented in this paper emphasise the importance to the UK of retaining a deep level of integration with the EU. They explain the UK’s attachment to the concept of a deep and comprehensive free trade agreement. As an aside, the figures also demonstrate that the financial settlement agreed by the UK – a one-off payment in the region of £40 billion – may be good value, if it enhances the prospects of such an agreement.

The results also highlight some of the constraints to the UK’s global ambitions. In particular, there are tensions between the extent to which the UK wants to retain a deep, friction-free trade relationship with the EU and the extent to which it wishes to pursue an ambitious free trade agenda with the rest of the world. Countries that currently have a FTA with the UK via the latter’s membership of the EU are likely to see the UK in a different light once it leaves the EU.

Notes

[1] For a more detailed discussion, see Peter Homes and Michael Gasiorek, “Grandfathering free Trade Agreements and Rules of Origin: What might appear bilateral is infact trilateral”, https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2017/09/27/grandfathering-ftas-and-roos/