After the morning after: what next for UK trade policy?

In the aftermath of the UK General Elections, in which the Conservatives won 364 out of 650 seats in House of Commons, the question that arises is what this means for the UK and the EU. “Getting Brexit done” was, after all, the platform on which the Conservatives campaigned. And beyond Brexit, there are wider questions as to how the UK will position itself in international trade.

No deal jitters – again?

With his large majority in the House of Commons, Prime Minister Johnson should have little difficulty in securing the ratification of the Withdrawal Agreement he negotiated with the EU in October. Assuming that the agreement is also ratified by the European Parliament, the UK will therefore cease being a member of the EU as of 31 January 2020. The ratification of the withdrawal agreement is an important milestone, not least because its contains a transition period until the end of 2020, to ensure that deep preferential reciprocal market access by the UK and the EU to each-others’ markets continues as before.

The first immediate challenge is that the a decision to extend, or not, the transition period needs to be taken as soon as 30 June 2020. Whether the UK and the EU agree to do an extension depends on the likelihood that they will complete talks on a new Free Trade Agreement, under the political declaration signed separately to the withdrawal agreement, in time for them to take effect once the transition period lapses. The time frames in the Withdrawal Agreement were carried over from the previous version signed in November 2018. That version envisioned that talks on new arrangement would begin in early 2019. These original time frames were deemed unrealistic. It is therefore even less likely that a FTA will be negotiated under the time-frames that now apply.

Expect, therefore, more political ructions about the possibility of no deal exit by the end of 2020.

What’s in the deal.

Setting aside process, the key question is what will go into the new deal with the EU. By comparison to its November 2018 predecessor, the October 2019 version of the political declaration conspicuously talks about a Free Trade Agreement. The capitalisation suggests a rejection of a customs union as an option, consistent with the position taken by Mr. Johnson in rejecting the idea of a “customs territory” in the backstop protocol regarding Ireland and Northern Ireland.

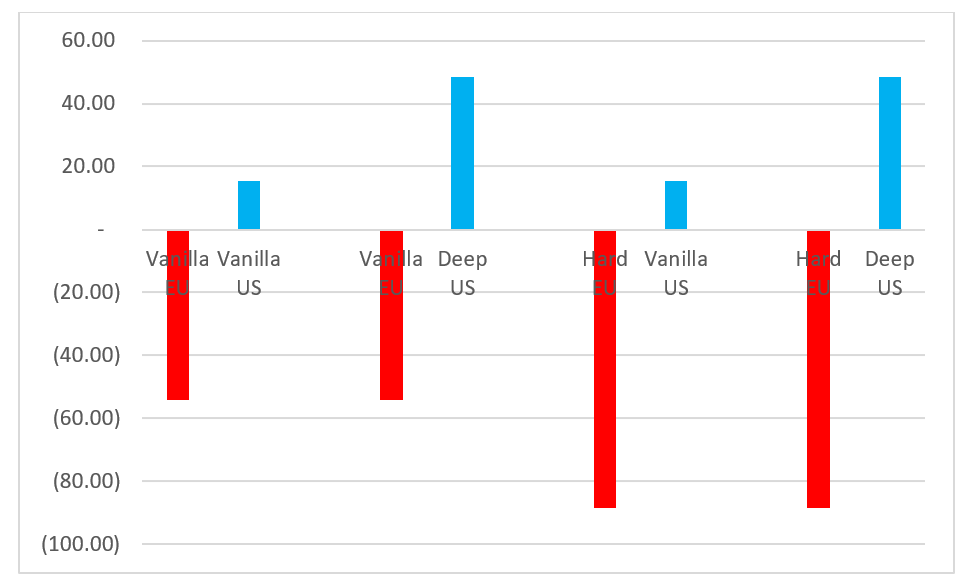

The key question is what depth of commitments the UK and the EU will be able to enter into. A Canada-type arrangement would lead to substantial losses relative to an EEA-type agreement (see the middle column of figure 1 below). The latter would involve a commitment to all pillars of the single market, something Mr. Johnson has rejected. The issue will therefore be how far the UK and the EU can agree on deep liberalisation in services and goods.

The EU would need to soften its requirement that the UK, if it rejects the single market, must necessarily go for a weaker Canada-type agreement. Faced with Mr. Johnson’s political majority, EU members may be minded to agree to a deep and comprehensive FTA (on goods at least, see left pilllar above). This was the sort of deal it had been hoping to offer Mrs. May had the latter secured a substantial majority in the 2017 elections, and the sort contemplated by Mrs May in her July 2018 White Paper

A deep arrangement would by definition require substantial commitments on regulations for goods, and possibly services. This in turn would require that Mr. Johnson depart from his script.

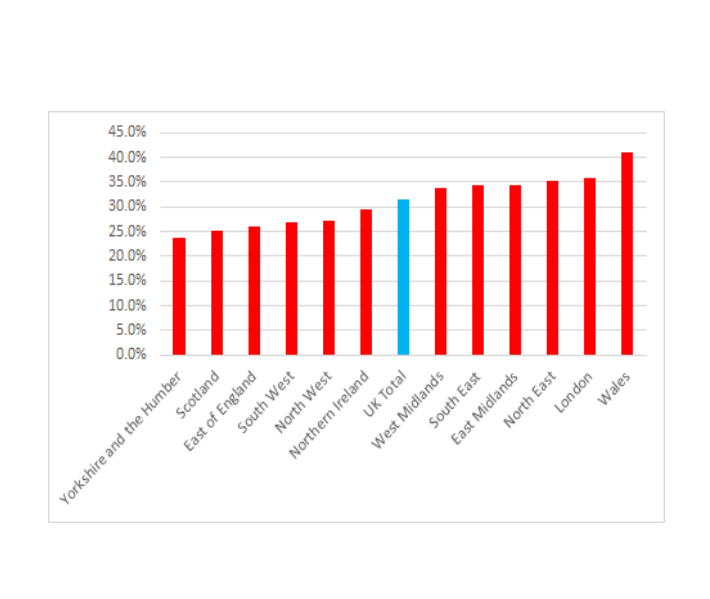

Again, the politics might favour that. Figure 2 shows the openness to trade (the ratio of trade to regional gross value added) of different regions within the UK. Crucially, the midlands, north east, and Wales (along with London and the South East) show higher degrees of openness than the UK average.

For these three regions, this openness is driven by goods trade, with the EU the dominant partner, particularly in sectors like automotives. These three regions provided important parts of the political swing to the conservatives, and would be disproportionately affected by losses from a weaker FTA with the EU, given the intricate nature of cross-border supply chains, and the impacts of both tariff and non-tariff measures. Moreover, in those parts, notably post-industrial towns, where there is a heavy reliance on public services and spending, a hard brexit may prove to be damaging via its effects on public finances.

The politics of the election therefore point to the political economy advantages of a deeper FTA and a quick resolution to the question.

What do we do on services?

Services account for 80% of the UK economy and are the fastest growing part of its trade. Yet services have not received a level of attention that is in any way commensurate with their importance. This is partly because the UK has pursued the idea that it would accept to leave the single market for services if it could also exit single market disciplines on the movement of people.

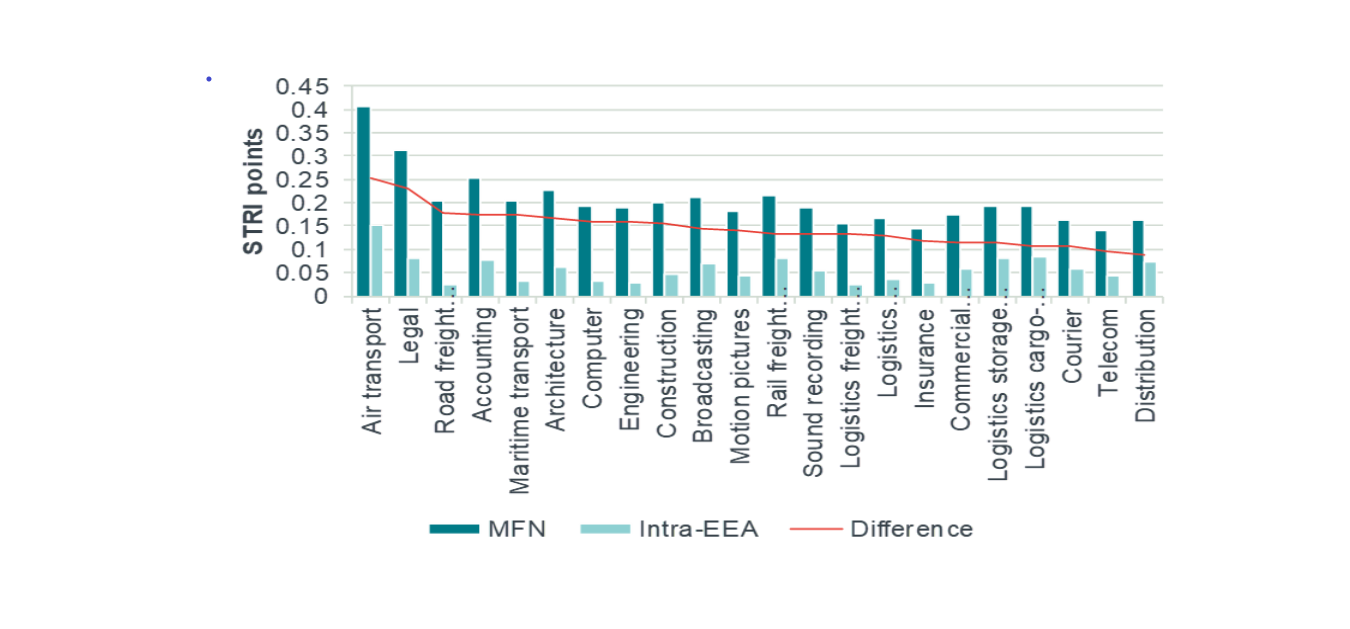

One of the features of services trade liberalisation is that there is very little difference between the degree of liberalisation countries implement on a MFN basis (i.e. applicable to all parties) and that offered through free trade agreements. The main exception to this is the EU single market. Even though services liberalisation has been uneven across the European Union, it is significantly deeper than anything else on offer. Hence even if the UK were to leave the EU with a Canada-style free trade agreement, it would take a hit to its services trade which would be very close to what it would take if it left with no deal at all.

Figure 3 below shows the differences in services trade restrictions by sector, between the single market and MFN levels. The higher the restrictions, the lower the level of liberalisation. We can see that the differences are particularly pronounced for certain transport and professional services sectors

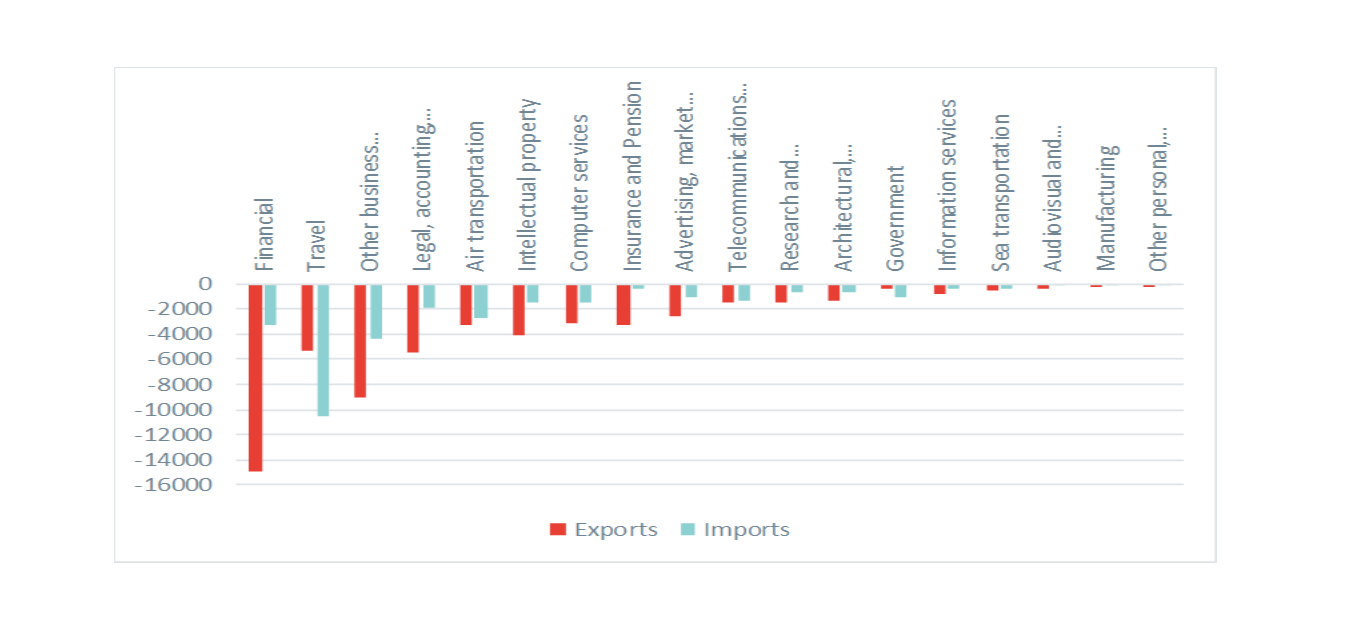

In absolute terms, sector losses from a weak FTA or a no-deal services exit would be largest in financial services, given the size of the sector. Travel services is one area where the import effect (UK citizens travelling to EEA partners) significantly dominates UK exports.

Remember the other no deal: the UK and non-EU trade partners

The Withdrawal Agreement contains a transition period in which the UK’s access to the EU single market continues unchanged. But that transition period does not extend to the preferential access the UK currently has in markets with which the EU negotiated free trade agreements. In some cases the UK has negotiated replacement agreements. But in important markets such as Canada, Japan, Singapore and Turkey, this is not the case.

UK exporters therefore face a no-deal scenario with these markets. In Canada, for example, exports of motor vehicles, aircraft components and machinery face tariffs of between 6 and 9%. In Japan, the main issue is non-tariff measures that apply to these products. Again, the political economy of this situation is relevant: the industries mentioned play an important role in regions that swung to the conservatives, and more traditional conservative strongholds.

Negotiating replacement agreements thus ought to be a priority for the UK government. The difficulty is that partners in question have little immediate incentive to negotiate with the UK. This is because they can pocket such market access gains as they have via current arrangements with the EU for as long as the UK implements the EU’s customs code (i.e. as long as it is under transitional arrangements, and longer in the case of Northern Ireland under backstop arrangements).

New deals?

President Trump greeted news of the Conservative’s win with a promise that the US and the UK would soon agree a massive deal. He said this would be more lucrative than a deal struck with the EU. The underlying economics suggests this is very unlikely to be the case, unless the UK signs a particularly weak deal with the EU and at he same time manages to replicate single market-type arrangements with the US (see figure 3 below). Given that single market arrangements took decades to negotiate, this is unlikely to materialise.

Setting aside political rhetoric, the key challenge for the UK is that any negotiations between it and the US will be about regulation, whether in goods and services. The USTR’s negotiating objectives seek, notably, non-discriminatory market access in UK services sectors. Even if healthcare is excluded from negotiations, that leaves open the question of regulatory reforms in areas like audiovisual services and broadcasting, transport and finance. In goods trade, food and agriculture will be key issues.

Besides the political sensitivities associated with these sectors, the differences in approaches between the US, on one hand, and the EU on the other will mean that it will be difficult for the UK to align with both.

Trade negotiations with partners such as Australia, New Zealand and (possibly) China have also been considered. Australia and New Zealand are currently engaged in trade negotiations with the EU. The UK might try to negotiate in parallel. The main challenges are: (i) negotiating capacity given the other items on the agenda for the UK (ii) the likely inclusion of MFN clauses in the EU’s FTAs (under which a country the grants a non-EU party more favourable treatment than was negotiated with the EU must then extend that treatment to the EU) would mean that the UK is unlikely to be able to complete a deal with these countries until their position with the EU is substantially settled. Bearing in mind that a market of 450 million people will be more attractive to trade partners than one of 66 million.

Dealing with a tricky environment for international trade.

The fallback option for the UK to any of the preferential agreements highlighted above is to trade on Most Favoured Nation terms under the WTO. Setting aside the loss of preferential access this would entail, one of the difficulties with this fallback is that the security of these rules has been weakened by the on-going crisis at the WTO surrounding dispute settlement. By vetoing the appointment of judges to the WTO Appellate Body, the United States has chosen to impede the functioning of the dispute settlement system, since any panel decision that is appealed will be left in limbo. Lack of enforcement reduces the value of WTO commitments.

The crisis comes at a time when trade restrictions have reached their highest levels since the WTO started monitoring them continuously in 2012. The UK is thus in the position of leaving the EU – and the security of its rules – at a time at which the outlook for international trade is sombre. One of its priorities might therefore be to strengthen the operation of the WTO. It could for example use its position outside the EU to act as honest broker in collaboration with similarly-minded countries.

Further down the road less travelled?

The economics of Brexit remain challenging, something that will not change simply by virtue of electoral arithmetic. Timelines that are compressed for political reasons will likely leave the UK facing unpalatable outcomes. Perhaps paradoxically, some of the political forces that emerged from the recent election may increase the political payoffs from treading carefully.