An enhanced UK-Switzerland FTA: what are the main issues?

The UK and Switzerland have announced that, after a year of exploratory talks, they would launch negotiations on an “enhanced” Free Trade Agreement (FTA). The two countries also announced that they would try and conclude a mutual recognition agreement on financial services by the end of 2023. We consider some of the issues.

Some quirky trade patterns

The UK and Switzerland have a significant trade relationship. The UK accounts for around 5-6% of Swiss goods exports and around 6% of its services exports. Meanwhile Switzerland accounts for around 3% of UK good exports and around 4% of UK services. After the USA, it is the second largest non-EU services export destination for the UK. As discussed below, financial services are a key part of the story.

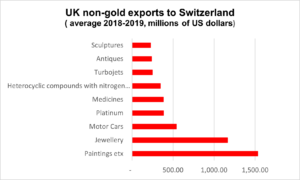

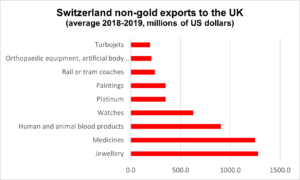

The headline data hide some curious quirks. Gold and art work (paintings, and sculpture) play an important role in goods trade in both directions, and particularly in Swiss exports. Both are connected to financial services. London in particular acts as a centre for gold-backed exchange traded funds, and as a hub for trade in art. While Switzerland acts as a hub for wealth management and clients seeking alternative means of storing value.

Setting aside trade in gold the charts below show an eclectic mix of traded products. Major UK exports include medicines and chemical compounds, but also turbojets and motor vehicles, and jewellery and antiques over 100 years of age. Despite what Orson Welles might have you believe, the Swiss produce more than clocks and watches. Precision medical equipment (such as orthopaedic products, artificial limbs and hearing aids) rival medicines and other goods from medical and biotech industries (such as human and animal blood products). And, perhaps a little unexpectedly, turbojets and tram and rail coaches.

The patterns, and especially similarities in products, point to the value of trade policy provisions that help knowledge based industries such as bioscience and chemicals industries, and precision manufacturing. Precision medical appliances like hearing aids also raise interesting trade policy issues since they are increasingly produced via 3-D printing. They obviate the need for physical cross-border flows (though they may stimulate classical trade in complementary products), and introduce new supply chain dynamics and opportunities, including in the country of destination.

The historical context

Switzerland and the UK would not start their negotiations from a blank slate. An agreement signed by Switzerland and the then EEC in 1972 covered trade in industrial goods. Once the UK had decided to leave the EU, the UK and Switzerland agreed to a continuity agreement. This rolled over the free trade agreement on industrial goods.

It also rolled over some, but not all, the bilateral agreements the EU and Switzerland had agreed in the late 1990s and 2000s. The ones rolled over included those on certain types of processed agricultural products, government procurement, mutual recognition, non-life insurance services, and aspects of trade facilitation.

Importantly, the continuity agreement did not include free movement of people provisions. Nor did it include services other than non-life insurance. That is why in announcing the exploratory talks, both Switzerland and the EU focused on services, and financial services in particular.

The importance of services trade

Financial services, along with professional services, dominate the landscape….

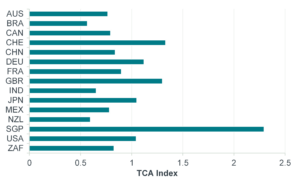

Financial services are thus firmly in the spotlight. Switzerland accounts for around 3% of UK financial services exports. It also accounts for around 5% of professional services exports which are often closely tied to financial services. Measures of comparative advantage (see chart below)[1] suggest that the UK and Switzerland are among the most competitive suppliers of financial services globally, along with Singapore.

One of the reasons that Switzerland and the EU did not manage to conclude a bilateral agreement on financial services was because of differences over the principles behind such an agreement. The Swiss did not want to follow an approach based on equivalence, in which Swiss regulations were assessed to the extent their content aligned with EU rules, and which implied an obligation to continuously align Swiss regulations with EU ones.

Rather, the Swiss wanted an approach based on mutual recognition, and an assessment that the effects of regulatory frameworks would provide the same outcome regardless of differences in content. That approach also tallies with the UK’s position of avoiding equivalence-based approaches and “dynamic alignment”. Now that the UK is outside the EU, both parties see an opportunity in to strengthen reciprocal liberalisation by agreeing a mutual recognition framework. This is why the matter appears to have been fast tracked.

Under WTO rules on services, countries are allowed to conclude mutual recognition agreements outside the scope of a comprehensive services FTA. A more broader set of liberalisation measures, say on regulatory cooperation, improved market access for cross-border trade and investment, would need to be part of a financial services chapter of a FTA.

Negotiations on financial services come at a turbluent time for Switzerland, in the wake of the near collapse of Credit Suisse and its subsequent acquisition by UBS. The episode prompted much soul-searching in Switzerland, on a number of fronts. That includes the extent to which the acqusition affects competition in banking services in Switzerland. Here trade policy may have a role to play. OECD data suggest that Switzerland’s commercial banking sector is more restricted than the OECD average. Much of this is driven by restrictions on foreign entry, including more stringent licencing criteria for foreign banks and restrictions on branching. These matters could be candidates for negotiation, and would complement work on mutual recognition

…But are far from the only story

One of the big ticket items should be the movement of people. When the UK was part of the EU, Switzerland and the UK both enjoyed free movement of people with each other, and the access to skills and labour markets that went with it. Neither party is likely to return, mainly for political reasons, to the pre-Brexit state of affairs. But an ambitious agreement would be important for two economies that rely on talent in interconnected value chains, in areas such from finance, professional services, life sciences, chemicals, and precision manufacturing. Steps include streamlining the operation of economics needs tests, and implementing generous duration of stay provisions for various categories of workers and suppliers, as well as investors. These measures could also be supported by initiatives on research collaboration.

Movement of people is connected to the question of collaboration on science and research and development. The UK and Switzerland have taken steps to deepen their partnerships in these areas. Both are driven by concerns that their partnerships with the EU could be affected by the broader dynamics of their respective relationships with the EU (see below).

Both the UK and Switzerland also have an interest in services that provide environmental functions. A range of services are concerned, from waste management and recycling to archtecture, engineering, and computer services. Given both country’s interest in circular economy matters, and commitments to environmental and climate goals, the FTA could look to enhance trade in these areas. In this respect, barriers to the movement of people are a key obstacle in both countries. The delivery of environmental services depends on knowledge inputs, so addressing these barriers would be beneficial.

Finally, digital trade is an issue of interest to both parties. The share of digitalised sectors in trade is significantly higher for the UK than it is for Switzerland (50% versus around 30% according to OECD data) But major sectors of interest to both, such as financial and professional services, are heavily digitalised. Both also have an interest in developing rules on matters such as Artificial Intelligence that balance public policy concerns on matters such as privacy and fundamental rights, with the role taht AI can play in innovation. A FTA could provide a forum for regulatory collaboration on these issues.

A goods story as well

Services play an important role in the export of goods for both countries. Around 30-35% of value added in exports for both countries is accounted for by services. Making services sectors more competitive through liberalisation therefore ought to help goods exports, and manufactures in particular.

With industrial tariffs already largely addressed through the existing agreement on industrial goods, the main area for progress would be on non-tariff measures such as rules of origin and issues of regulation.

Non tariff measures

On rules of origin, the main issue for the UK and Switzerland is how their bilateral agreement takes into account the fact that their value chains span into the EU. When the UK was part of the EU, this was not an issue. Post-Brexit, to preserve a seamless operation of tripartite value chains, the UK and the Switzerland agreed, under the continuity agreement, to a “trilateral approach” to rules of origin. That is, one that would allow for the recognition of inputs sourced from the EU to count as originating content (and thus eligible for preferential treatment) in UK-Switzerland trade. That included the commitment to update rules of origin for UK-Swiss trade once UK-EU rules of origin had been agreed. This will be an early priority for negotiators. The main challenge is that to be truly trilateral, the process needs also to have the assent of the EU as well, so that Swiss or UK content in value chains to the EU are eligible for preferential treatment.

On regulatory issues, existing arrangements rolled over aspects of the Swiss-EU mutual recognition agreement (MRA). As applied between the UK and Switzerland, the MRA currently covers motor vehicles, and matters of importance to pharmaceutical and related industries. Specifically good laboratory practice and good manufacturing practice for inspection for medicinal products and batch certification. The latter is not simply a mouthful of jargon: standards in this area are central to the effectiveness and safety of health products and medicines. Streamlining them helps to ensure that value chains spanning both countries operate efficiently.

Much of the focus of any upcoming negotiations would therefore lie in extending the scope of MRAs to other sectors and activities. One of these could be medical technology and devices. The sectors are important to both countries. As seen previously, for Switzerland, exports of some of these devices regularly fall within the top 10 export products to the UK. These sectors typically involve small and medium enterprises. For SMEs the administrative burdens of regulatory compliance can be particularly high, meaning that measures like MRAs can be particularly valuable.

From a Swiss perspective, a MRA could be particularly valuable, both to exporters and domestic users. This is because Switzerland no longer benefits from MRA coverage with the EU, its leading trading partner, after the EU refused to update the bilateral MRA to reflect new regulation in the area of med-tech. The refusal was tied in to Switzerland’s hesitancy in signing an overall framework agreement with the EU to govern Swiss-EU bilateral relationship. The UK can draw on these developments to conclude a MRA that would also be in its interests.

Everything but farms?

The trade agreement between Switzerland and the EU, which was then rolled over to the post-Brexit Switzerland-UK agreement, covers agriculture in a limited manner. This largely reflects Switzerland’s heavily protectionist approach to its farmers. The OECD estimates the total value of Switzerland’s support to producers at over 1% of GDP (the sector itself accounts for around 0.7% of GDP) compared 0.3% for the U.K. and 0.6% for the EU.

It is unlikely that agriculture will be a prominent part of the discussions given the position of farming lobbies in both countries. The National Farmers’ Unions positions on UK FTAs have been largely defensive. With many of the UKs recent FTAs or negotiations involving countries that are large agricultural exporters, they have been largely limited to airing grievances about increased import competition. They will likely not need to worry about that under a FTA with Switzerland.

What may worry the Swiss though is any perception that the UK could weaken food safety standards in a bid to strike FTAs with other partners, such as the USA. FTAs can be a politically sensitive topic in Switzerland. Its FTA with Indonesia was brought to referendum after a public petition driven by concerns around agriculture and sustainability. The FTA was narrowly voted through but it did serve as a cautionary signal to Swiss negotiators on handling the agriculture-sustainability nexus in future in future FTAs.

Not just a two-way negotiation

A bit like Banquo’s ghost, the bilateral relationship both Switzerland and the UK respectively have with the EU will be the unsettling presence at the negotiating table. Both parties currently have a strained relationship with their largest trading partner. UK-EU tensions relating to various aspects of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement – most visibly over Northern Ireland – are well known.

Switzerland has thus far not signed up to a bilateral framework agreement that the EU thinks would put Swiss-EU relations, currently governed by a myriad of bilateral agreements, on a firmer legal footing. Swiss opposition largely echoes concerns raised by the UK in its negotiations with the EU: the role of European law and the ECJ in disputes; and concerns over whether a framework agreement would undermine measures Switzerland has in place to mitigate the impact of free movement of people (covered in a specific bilateral agreement) on social security benefits and on Swiss salaries.

In that context, both the UK and Switzerland probably see a deepening of their relationship as a way of demonstrating to the EU that they have “outside options”. This is particularly true in financial services, where both are powerhouses. Financial services – like services generally – were superficially dealt with in the UK-EU TCA (compared to their treatment under single market arrangements) and as observed above there is no bilateral agreement between Switzerland and the EU. Besides creating market access opportunities, the UK and Switzerland probably hope that deepening financial integration between the two could push the EU towards what they consider to be a more pragmatic approach to regulatory cooperation. Similarly, concluding MRAs in advanced manufacturing and knowledge based industries could strengthen cross-border value chains in sectors where both countries have a strong comparative advantage.

The de facto “trilateral” aspects of the negotiation won’t be easy to navigate. The rules of origin issue discussed above is one such example. Data flows are another such example. Both Switzerland and the UK are currently considered by the EU to be adequate for the purposes of the GDPR. The UK is however in the process of reassessing its national data strategy, and may well choose a different path to GDPR. Switzerland for its part is likely to remain very much within the frame of the GDPR and there is little appetite to depart from it. Agreeing on a framework that allows both parties to manage any future divergences will present a challenge, but given the centrality of data to sectors such as financial services, this is of high importance.

Summing up

The potential UK-Switzerland FTA negotiations would come at a sensitive time for both parties. They both need to navigate the economic imperative of maintaining close ties to their largest trading partner, the EU, but face significant internal political constraints on the manner in which they do that. Whether a UK-Switzerland FTA helps to change negotiating dynamics with the EU is unclear. What is perhaps more clear is that there will be opportunities for both the UK and Switzerland to try and break new ground in sectors such as financial services, skills and movement of people, and regulatory cooperation. The long shadow cast by the EU means these bilateral initiatives will likely have trilateral (i.e. EU-facing) implications, which will require judgement and analysis on how best to pursue any trade-offs.

[1] This graph shows a measure of comparative advantage known as total comparative advantage. Values in excess of 1 indicate comparative advantage, and the higher the score the stronger it is.