On 27 March, the House of Commons voted on eight approaches to “Brexit”, as alternatives to the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated between the UK and the EU in 2018. Votes on these plans were indicative i.e. they were not binding on the government. In the event, all motions were rejected, including motions in favour of a no deal exit, the revocation of article 50, and on putting any exit deal to a public vote. Critics observed that parliament has now failed to unite on any form of Brexit with or without any form of deal, on holding another referendum on Brexit, or revoking Article 50 of Lisbon Treaty that formally triggers Brexit.

At this stage, the only options on the table remain the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated in 2018, and leaving without an agreement. The latter being the default set under Article 50, which continues to run its course. In an attempt to rally support around the Withdrawal Agreement the Prime Minister announced she would step down if and when it had been passed by Parliament, and prior to the next phase of negotiating the shape of future arrangements between the UK and the EU under the terms of the political declaration that accompanied the Withdrawal Agreement. That announcement appears to have raised the level of support for the Agreement among hard-line Brexiters, though whether that is sufficient to get the Withdrawal Agreement through at the third time of asking remains unclear.

Going through the motions?

Setting aside the motions focusing specifically on a confirmatory referendum and revoking Article 50, the indicative vote process allows an assessment of options for the terms on which the UK would leave the EU, and future arrangements. While all these were rejected, it is important to remember that even if the government’s Withdrawal Agreement is passed, that only sets out the terms of the UK’s departure from the EU. The UK’s future relationship to the EU needs to be negotiated under the process envisioned in the political declaration. That distinction was blurred in the indicative vote process, since several of the options sought both to determine the terms of withdrawal and the end-outcome of the future negotiation. That may in part account for their rejection. Consequently, they and others are likely to be back on the table at some point in the future. Especially if we bear in mind that unlike the Withdrawal Agreement, the political declaration is not a legally binding text.

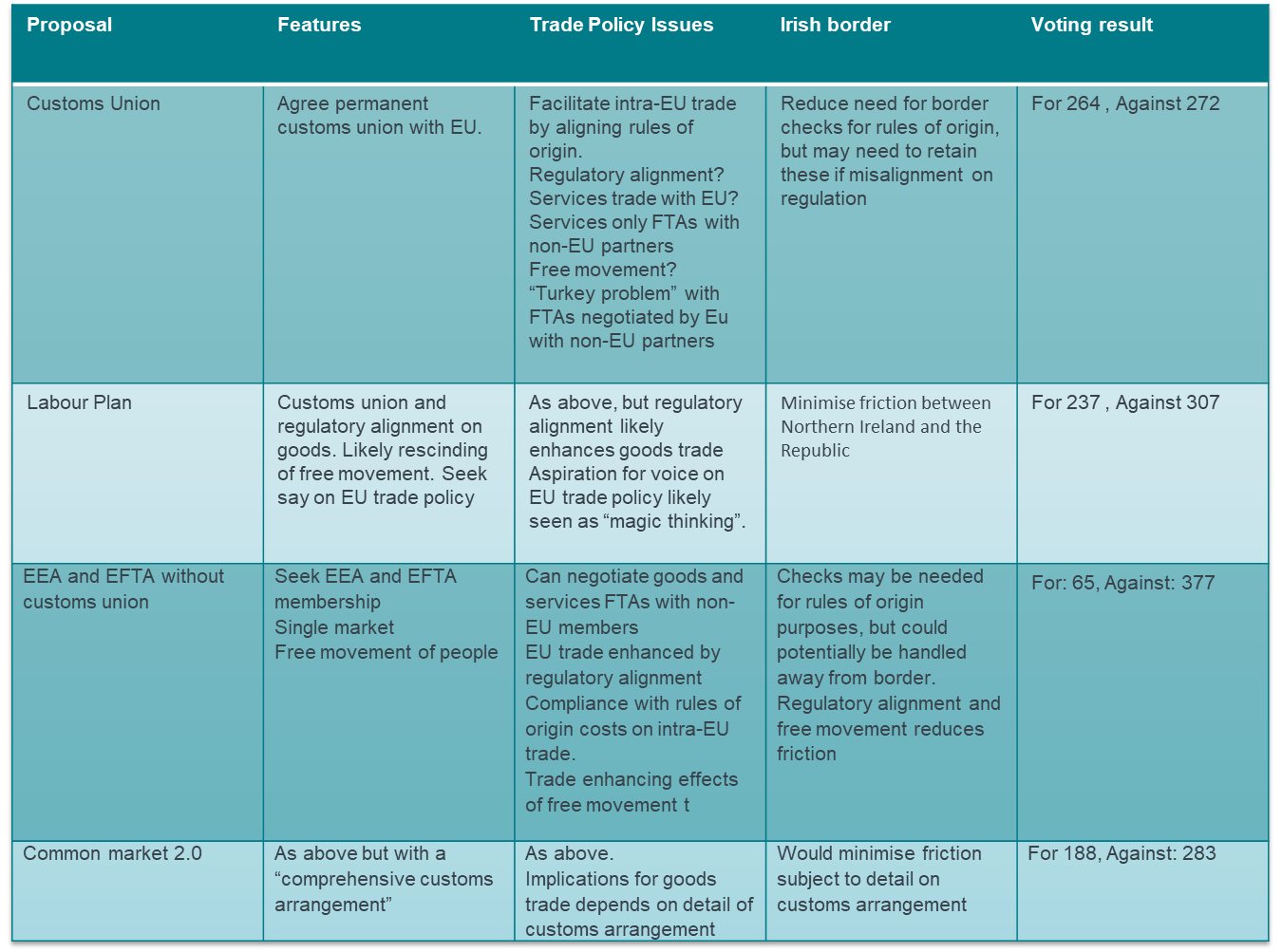

The tables below sets out the main alternatives for future arrangements presented to parliament. For completeness, we also add options that were not voted on, including the Canada Plus option that has been floated in the past. We leave out no-deal, and motions to do with the revocation of article 50 or a second referendum. We focus on implications for trade policy, because the question of the UK’s trade policy singled out in both the current withdrawal agreement and the political declaration. We also look at the implications for the Irish border given its prominence in recent debates.

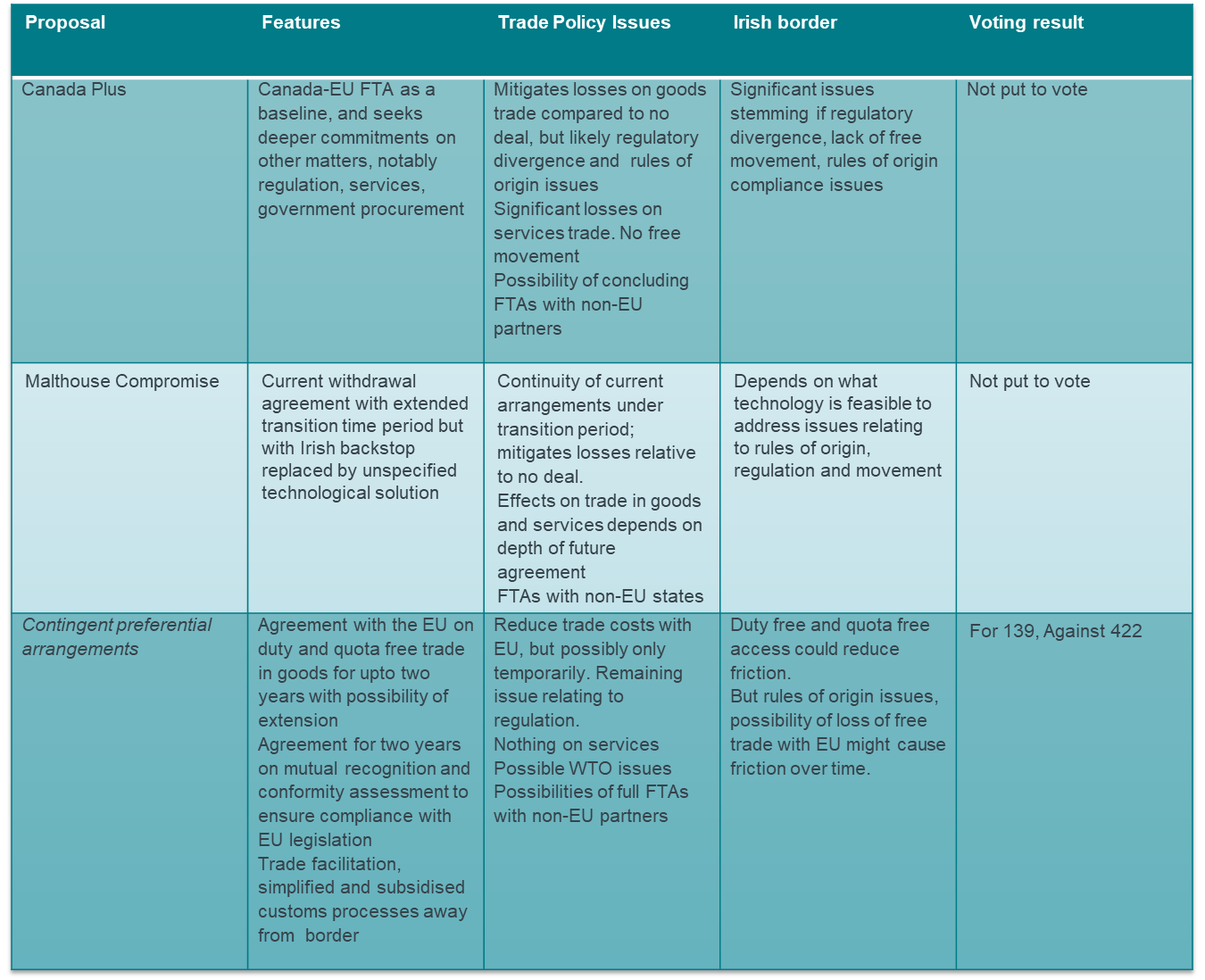

The options can be grouped into two broad categories. The last two that are listed, the Malthouse compromise proposal and the contingent preferential arrangement proposal focus mainly on the terms of withdrawal. They do not commit to particular, or indeed any, view on the future arrangements between the UK and the EU other than that they seem to represent a rejection of a future customs union. We say “seem” because the genesis of these two proposals lies in a rejection of Irish backstop, and that the sponsors of these two proposals are particularly hostile to the notion of a customs union embedded in the backstop, which will also serve as a baseline for future arrangements.

All the other proposals essentially try to specify the terms of separation and also the shape of the future arrangements. Under the settlement agreed between the government and the EU, the future arrangements were to take place within the framework of a political declaration that set out broad principles, without committing in detail to the final destination.

What’s really on the menu?

What are we to make of these plans? Much of the quantitative analysis for various options can be found elsewhere on this site (see in particular here, here and here).

All the proposals envision free trade in goods between the UK and the EU. The Customs Union plan and the Labour Plan are close, though the latter is explicit on the fact that it seeks a deep level of integration. It supports “close”, but presumably not complete, alignment on rules. By “close”, it is likely that under this plan the UK would align itself to regulation that has a particular impact on cross border flows and supply chains. This is both for economic reasons and in order to preserve friction- free trade between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Areas in which the UK may not seek alignment include state aid rules, a position that reflects the current Labour regime’s predilection for economic interventionism.

It is possible that proponents of the customs union plan would also seek a deeper level of integration on regulatory and other matters. Deep customs unions are essentially a Turkey plus option i.e. the UK would have a customs union like Turkey does, but go deeper on harminising regulation. The customs union would rule out the possibility of free trade agreements on goods with non-EU member states. It also means that the UK will need to implement any preferential access that the EU gives to non-EU partners under its FTAs, without any guarantee of getting access to these partners. Turkey is in exactly this predicament. The Labour plan proposes that the UK will have a voice in the EU’s external trade policy. But this seems to be the stuff of fantasy. The EU jealously guards it common commercial policy which it sees as its most potent instrument in projecting power.The Commission also guards its competence in this area, and is extremely reluctant to cede any control to national governments of member states, let alone one outside the EU. And given that the likes of Turkey would dearly love to have a voice, it is hard see such a proposal going anywhere.

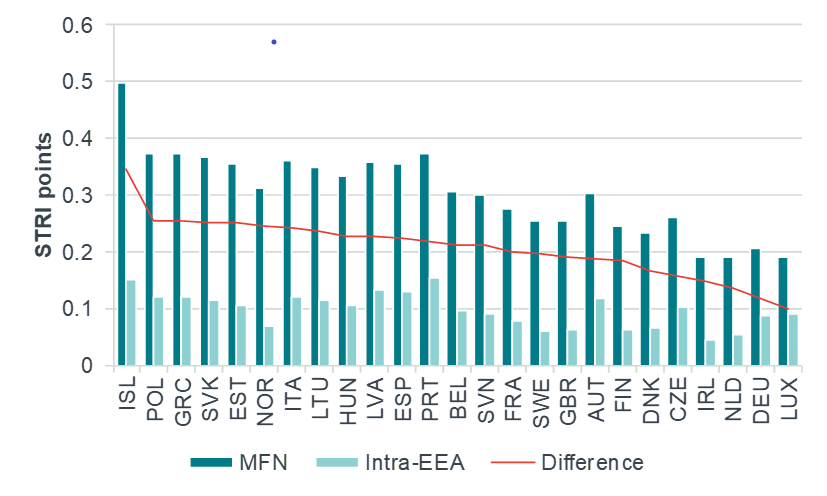

The customs union plans came closer than the others in securing a majority, suggesting this approach may have potential in any future negotiations. But a major question that both leave open is what will happen on services. The non-committal approach is close to the current government’s position: to exit the single market for services in return for allowing the UK to exit single market disciplines on the movement of labour. But as reported elsewhere, the effects of losing single market access on service can be significant. New data published by the OECD allows us to compare intra-EEA services restrictiveness to the level of restrictiveness applied by EEA countries to countries outside the single market (labelled as “MFN restrictions”). Some preliminary estimates of these differences on a trade weighted basis for selected partners are presented below.

The differences are significant and moving away from EEA levels to MFN levels would have a large impact on UK services trade. These can be mitigated to the extent that the UK negotiates services liberalisation. But these commitments would need to be much deeper than those that are present in FTAs currently in force between the EU and, say Canada, as these largely lock in MFN levels.

In light of this, two other proposals (the EEA/ EFTA proposal and the Common Market 2.0 proposal) look to maintain participation in the single market. The EEA/ EFTA proposal dispenses with the notion of a customs union, which allows the UK to pursue FTAs in goods and services with non-EU members. The proposal also accepts free movement. Because the loss of free movement reduces access to skills, it acts as an implicit tax on UK exports regardless of whether these go to the EU or elsewhere. Hence maintaining free movement is a natural complement to the idea of an independent trade policy.

The EEA/ EFTA option would require checks to make sure rules of origin requirements are satisfied. This could lead to friction at the Irish border. But equally, if movement of people and regulatory compliance are not issues, handling rules of origin matters through a technological solution may seem less far fetched than under other proposals.

Perhaps with this issue in mind, the Common Market 2.0 proposal supports, in addition to EEA membership, a comprehensive customs arrangement. But what this means is not clear. It may be something like the mirroring arrangements the government proposed in its July 2018 White Paper. But these create many administrative issues, and it is unlikely that the EU will accept a non-standard, legally untested concept in any agreement. This is indeed why the EU, while accepting a withdrawal agreement that was much closer to the UK government’s proposals than its own starting point, nevertheless proposed a customs union (a tried and test legal concept) as part of the backstop.

Both the EEA/EFTA proposal and the Common Market 2.0 proposal were roundly defeated. Under both, a significant shift in the government’s red lines would be needed, specifically on free movement. A shift in the current opposition’s attitude on the matter would also be needed. Thus progress on these matters would require a change to the parliament’s current political configuration.

The features and shortcomings of the Canada plus option have been discussed here.

As already observed, the Malthouse compromise has a limited objective i.e. of retaining parts of the withdrawal arrangement while dispensing with the backstop. The difficulty – other than the hand-waving regarding the technological solution – is that the customs union proposed by the backstop puts a limit on the losses that UK would face on exit. That is, it provides a default option that protects the UK from particularly bad outcomes. Losing the backstop means losing that limit on losses.

The contingent preferential option, and variants thereof, could raise substantial issues of WTO law depending on how this is implemented. To be WTO compatible there would need to be some sort of joint treaty instrument agreed between the parties (even if is a 1-2 page statement agreeing duty and quota free trade). It is not a no-deal option. Other drawbacks are similar to the ones described for the Canada FTA option, though likely deeper in magnitude.

Was it as good for EU?

In terms of economic outcomes, the options proposing a continuation of single market arrangements will likely have the smallest adverse effects relative to membership. They would also require a substantial change in political red lines in the UK. It is clear from the voting results that a coalition for such a change cannot be created under the parliament’s existing configuration.

Another challenge, is that implementing any of these arrangements would equate to agreeing simultaneously the terms of withdrawal and the shape of future arrangements. Sorting the detail of that out would require time and hence an extension of the article 50 process. The EU would also have to move away from its insistence on sorting out the terms of withdrawal first and the future arrangements after that. It should also be observed that none of the two Customs Union plans, the Common Market 2.0 or the EEA/EFTA arrangement would be ruled out by signing the Withdrawal Agreement as it is, and working on the basis of the existing political declaration. The two customs union plans present direct lines of continuity with the Withdrawal Agreement, and there is sufficient flexibility in the political declaration to accommodate the two plans seeking continuity of integration with the single market. That in turn raises the question as to whether the proponents of these approaches are better of clearing the decks first by passing the Withdrawal Agreement, and then using the time to build consensus on future arrangements, perhaps on the back of a parliamentary elections, rather than trying to negotiate the end-state at the outset.