Bridge over troubled waters? The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement and the future of UK trade policy

After long and arduous negotiations, the European Union and the United Kingdom signed a Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) on 24 December 2020. The agreement establishes the basis for the relationship between the two parties from 1 January 2021 onwards.

The TCA largely corresponds to what we projected close to 3 years ago, given the starting points of both parties and their respective “red-lines”. It resembles in some instances the types of preferential agreements that the EU has signed with other trade partners. But on a number of specific issues it departs substantially from such agreements. This is particular visible in relation to “level playing field issues” of regulation, subsidies, environmental and social and labour market matters. The mechanisms proposed for subsidies, notably, are complex, multi-layered and go far beyond anything present in the EU’s other trade arrangements. The overall institutional arrangements for governance and dispute resolution also contain aspects not seen elsewhere. However the TCA may be characterised, a “Canada-type agreement” it is not.

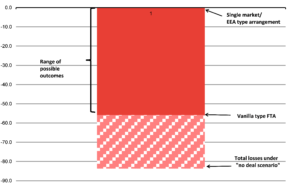

The signing of the agreement was met by relief by both sides. It avoids the serious economic consequences that might have arisen had both sides failed to come to any agreement. But because the TCA represents a substantial reversal of integration between the UK and the EU, substantial trade and economic losses compared to the counterfactual of single market membership are still expected. The OBR projects the outcome could lead to growth being 4% lower than otherwise (compared to 6% in a no-deal scenario). In the graphic below, which represents annual losses to UK services and goods exports, the TCA lands very close to the “vanilla type FTA”. It avoids the losses in light red associated with a no deal outcome, but still exposes the UK to the much larger chunk of losses in dark red.

Clearly then , the signing of the TCA presents both parties with a series of related challenges. For the UK, the key questions are how far the TCA can act as a basis for its future prosperity; and, following from this, what issues the TCA raises for the UK’s trade policy.

An agreement to keep talking

The American political economist Lester Thurow once (wrongly) dismissed the GATT[1] as the General Agreement to Talk and Talk. He would have enjoyed reading the text of the TCA. It contains a very large number of provisions dedicated to keeping both parties talking. Substantive negotiations, whether termed as such or coming under the guise of review and consultative provisions, will continue through the plethora of committees and working groups the TCA established.

This is not surprising. Simple economics tell us that when you have a G7- economy (the UK), and a market of 450 million people that includes other G-7 economies, on each other’s doorsteps, they will need to manage the interdependencies that arise between them. Indeed given that the TCA as it stands sets such a low floor on losses, they both have an interest in on-going negotiations.

Moreover, from the UK’s perspective, as argued below, there are limits as to how far it can pursue deep integration with the rest of the world on an substantially different track to that pursued by the EU. Finding common ground with the EU is likely to be an important condition for pursuing global trade ambitions.

Beyond tariffs

The TCA has helped to ensure the continuation of tariff and quota free trade between the UK and the EU. However, this achievement needs to be set against some other sources of trade costs. These include more complex customs arrangements, and potential effects on transport costs (particularly road haulage) of the partial loss of single market transport freedoms.

In a world of cross-border value chains, rules of origin constitute an on-going issue for the UK. These rules determine whether a good exported from the UK to the EU (or vice versa) is eligible for tariff free treatment. The TCA provides for full bilateral cumulation, allowing UK and EU producers to freely source inputs from across their economies collectively.

However, that still leaves the UK with the challenge of sourcing inputs from say Korea or Japan with a view to exporting to the EU. The UK will need to demonstrate a substantial degree of transformation of these inputs to qualify for tariff free treatment in the EU. The UK was not required to do this when it was part of the EU and its FTAs with Japan and Korea. This makes the UK potentially less attractive to Korean and Japanese investors using the UK as a potential base for exporting to the EU. Given the EU’s larger market, it may be more efficient for them to establish operations there directly.

The rules of origin issues will be important in a number of sectors that are of strategic value to the UK. Consider electrical vehicles and batteries for example. The TCA allows higher amounts of non-originating content for electrical vehicles and batteries for these, than it does for standard vehicles. That is good news for the UK. But these thresholds become more restrictive after 2023, and are then subject to further review. This case highlights how the TCA will require both an industrial policy response ( how to increase the share of UK or originating content) and a negotiation response (how best to adjust rules of origin in the future).

Playing on a level field with multiple rules

Negotiations on these matters proved to be major sticking point. On subsidies, the TCA appears to take a multi-pronged approach. It reproduces many of the principles of current EU state aid rules. While there is no system of ex-ante approvals, both the UK and EU are supposed to establish bodies that ensure that subsidies are administered in conformity with core principles governing state aid.

The UK government, and HMT in particular, should be very familiar with these principles as they closely follow those that are used in Green Book analyses of public spending. Indeed, departments like HMT might find these provisions useful as an internal discipline against forces pushing for expansive use of industrial subsidies.

The UK or the EU can challenge each other to demonstrate that subsidies conform to the principles set out in the TCA. The TCA also requires that each party allow for the use of courts so that an interested party (e.g. businesses or business associations) challenge the award of a subsidy.

The TCA then allows for other routes through which subsidies can be challenged. The UK or the EU may take remedial action if subsidies by the other are deemed to cause, or are likely to cause, adverse effects to its trade and investment interest. The imposed remedy can be subject to arbitration procedures if the party subject to the remedy contests its imposition. For subsidies and other level playing field matters, the TCA also allows for rebalancing action (i.e. a withdrawal of a commitment under a particular area of the agreement), which are subject to their own specific arbitration and dispute resolution processes. Finally, for industrial subsidies, the TCA allows the UK or the EU to take action in line with WTO rules i.e. through countervailing duties or through legal challenge at the WTO.

The many tiered approach set out under the TCA presents various challenges to the UK. On the one hand, that there are principles setting out what are acceptable subsidies should help the UK. It has a long track record of requiring government spending proposals to demonstrate how they correct market failures and are additional (and not a substitute) to private investment. Ensuring that these internal disciplines are maintained should put it in good stead to respond to EU questions about the rational for subsidies. At the same time, the fact that the provisions also allow parties to impose remedies on the basis existing of anticipated adverse effects creates a greater scope for challenge to subsidies under the TCA than was the case under EU state aid rules. In areas where industrial strategy rivalry is likely to heat up – green industries and knowledge industries, for example – it will be in the UK’s interest to: (i) structure its subsidies efficiently; (ii) liaise with the EU to ensure that the effects of these subsidies are understood and minimise adverse effects; and (iii) monitor the use by EU member states of subsidies.

Services and data

One of the reasons the TCA is likely to leave both parties, and especially the UK, worse off compared to single market arrangements is the treatment of services. From a UK perspective, leaving the single market for services was seen as the “price” to be paid for leaving single market provisions on free movement of people. When the position was first put forward, we observed that it made very little sense. Indeed, far from being a “reward” gained for the cost leaving the single market for services, the loss of free movement would infact likely exacerbate these losses. This is especially the case in knowledge-intensive sectors like professional services and finance.

The UK therefore has an interest in building on the TCA to deepen services integration with the EU. From an economic point of view, the logical approach would be to link reciprocal efforts to facilitate the movement of persons for the purposes of services and investment, on one hand, with stronger commitments to lower barriers to entry in each other’s markets, notably in areas such as financial and professional services, and air transport.

As services trade are heavily digitalised, the question of data is highly relevant to many of these sectors. This is also true of high value-added manufacturing. The TCA contains a specific chapter on digital trade. This contains commitments to avoid data localisation and restrictions on cross-border data flows, that go well beyond commitments found in most other EU FTAs. At the same time, the provisions explicitly allow for restrictions or conditions to be placed on data flows in line with wider policies for the protection of privacy and data governance (read: the GDPR). The challenge for the UK will be thus to secure an adequacy decision. Japan might provide an example in this respect: it concluded a FTA with the EU, and separately to that (and at a later date) obtained an adequacy finding.

Looking beyond EU

One of the ostensible prizes of Brexit was that the UK could pursue deeper integration with the rest of the world on a faster basis than the EU could. The reality is that the commitments the UK needs to meet to secure trade with its largest partner put limits on that. Securing free data flows with the EU will limit how far the UK can align to data governance regimes that depart significantly from the EU’s principles. Securing frictionless flows of food and agricultural products will constrain how far the UK can align with partners that diverge from the EU in their approach to regulation on these matters. Similar considerations apply to financial services.

On the other hand, some aspects of the TCA offer a basis for the UK and EU to exert joint leadership on international trade policy matters. The TCA contains very detailed provisions on the interaction between trade and climate change, and on sustainability and environmental issues more generally. Both parties could use the TCA as a demonstration of how bilateral cooperation can work on these matters, and as a template for international agreements. On matters such as subsidies, some of the principles in the TCA could be used as testing ground for developing multilateral approaches that overhaul current disciplines. Both the UK and the EU have a joint interest in this, particularly in response to the heavy use of subsidies by countries like China.

Interdependence day

The signing of the TCA put an end to a politically fraught period for the EU and, especially, the UK. But the signing of the agreement was, to borrow from Churchill, very much the end of the beginning. Indeed, reading through the TCA points to the magnitude of work on the table. If anything, the TCA highlights the interdependence between the UK and the EU; something which technological change and globalised production has only reinforced. While it puts an initial, and low, floor on economic losses, the TCA does provide opportunities for both parties to work bilaterally to improve their current respective provisions. In order to do that, policymakers will need a clear sighted view of their join interests. It will also require them to pay close attention to the feedback received by citizens and businesses on their experience of arrangements negotiated on their behalf.

[1] The General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs