This article describes the main types of agreements that have affected international trade, and their associated negotiating techniques. It traces the shift in focus away from negotiations concerned with tariffs, quantitative restrictions (QRs) and other types of direct restraints on trade towards broader-based negotiations and agreements which these days focus more on market access and regulation.

Types of agreements that affect trade

The main categories of agreements and negotiations considered are the following:

-

Negotiations on trade in goods

These are the oldest category of negotiations, going back to the Treaties of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation (FCN) which were negotiated by trading countries for several centuries. For example, the United States concluded its first FCN, with France, in 1778; but one might also interpret the Treaty of Perpetual Friendship between England and Portugal of 1373 as extending to trade. FCN treaties were generally bilateral, that is between two parties, and concerned with trade in goods – specifically tariff rates and physical restraints on trade – though they also extended to matters such as access for traders and protection for the shipping of partner countries. They established the basic techniques for international bargaining on tariffs, and laid down the fundamental trading principles of “most-favoured nation (MFN) treatment” and “national treatment”.

“MFN” is shorthand for the principle that a party to an agreement must offer to goods imported from its partner(s) tariff and other treatment which is no less advantageous than the best such treatment which it grants for the same classes of goods to any other nation in its trading relations. It is a straightforward commitment by the country not to discriminate between its different trading partners on tariff rates or other treatment.

“National treatment” means that once an importing country has charged any applicable customs tariffs on an item imported from a partner country, that item must be treated for all other purposes – such as excise duties, technical standards, labelling requirements, health standards, VAT etc. – no differently from the treatment accorded to “like” (i.e. essentially similar) items that are domestically produced.

-

Bilateral investment treaties (BITs)

BITs are a much more recent instrument, in which two nations enter into mutually agreed commitments concerning the flow and treatment of investment (including corporate establishment and both financial and physical investments) between themselves. The provisions of such agreements vary quite widely, and their coverage has evolved and widened over time, but the basic provisions are based on what is known as the “Dutch gold standard BIT”. They include commitments to MFN and national treatment for investors and investments of the partner countries; transparency of commercial legislation; protection against expropriation and nationalisation without compensation; rights for enterprises to transfer abroad funds such as capital, earnings and dividends; freedom of entry for key personnel; and provisions for dispute settlement, typically through arbitration by the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), or by any other mutually agreed means including action through national courts.

More recent BITs also often include wider provisions on corporate governance and prevention of corruption; environmental and labour protection standards; gender equality; technology transfer; and protection of intellectual property rights.

The first BIT (between Germany and Pakistan) was signed in 1959. The most productive decade for the negotiation of BITs was the 1990s, and by the year 2000 the tally had risen to about 1,900 worldwide. By 2012 there were more than 3,200. Not all these BITs were actually in operation (either through failure to ratify or because they had fallen into abeyance through political changes) but the majority were, and while the rate of signature of new BITs has fallen off year by year since 2000, it is still significant.

-

International standards-setting bodies

Since World War 2 there has been a proliferation of multilateral and intergovernmental bodies, particularly but not exclusively under the aegis of the United Nations, which set technical and commercial standards to which their member countries subscribe, and monitor observance. Such bodies include the International Standards Organisation (ISO); the International Labour Organisation (ILO); the World Health Organisation (WHO); the World Customs Organisation (WCO); the International Telecommunication Union (ITU); the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE – still known by the French initials of its former title); the International Maritime Organisation (IMO); and the UN Economic Commission for Europe, which sets vehicle standards. Such bodies all have impacts on the standards and conduct of international trade. They generally do not have direct enforcement powers, which are a matter for the constituent governments, and they cannot impose sanctions for non-compliance, but they work on the basis of joint action taken in the agreed public interest.

-

Free trade agreements (FTAs) and Regional trade agreements (RTAs)

The negotiation of FTAs and RTAs involving a number of participant countries that join together to increase their mutual trade is an essentially post-War phenomenon (although the UK had established a form of FTA through preferences for trade from British Empire countries as far back as the 18th century, and intensified it in response to the depression of the 1930s). The inability of the World Trade Organisation (WTO – see below) to negotiate further comprehensive trade liberalisation measures on a multilateral basis since 1995, has caused groups of countries to turn increasingly to FTAs or RTAs to increase their mutual trade and welfare. As at the end of 2017, 459 such agreements had been notified to the WTO, of which 287 were actually in force. Most take the form of free trade agreements designed to eliminate tariffs and other restrictions on trade between the parties, while individual members remain free to determine their own trade relations with non-members.

Some such agreements (pre-eminently the European Union) are customs unions, which go much further than FTAs in that they apply a common external trade regime of tariffs and other trade regulations to which all the members adhere. In both cases the WTO requires that “substantially all” the restrictions on trade between the parties must be eliminated. Although “substantially all” has never been satisfactorily defined, in practice it is taken to mean about 90% of all trade restrictions between the parties.

From FCNs to GATT

Tariffs have traditionally been a matter for individual governments, who were free at will to impose, vary or remove tariffs or to impose restrictions on trade according to perceived national needs. The objectives could be on one hand to use tariffs to protect specific productive sectors, or conversely to reduce tariffs to stimulate the national economy through increased competition in the market, or to reduce prices to consumers. Examples of such trade action include the UK’s Corn Laws, which restricted imports of grain to Britain between 1815 and 1846. These restrictions were aimed to protect the great farming estates, but they impoverished the general public. Other, even more egregious, examples include the high tariffs which major developed economies, predominantly in the US and Europe, imposed on imports in reaction to the international slump of the 1930s. The aim was to protect national manufacturing sectors and employment; the result was to reduce the volume of world trade by approximately half, to devastate industrial production and to impoverish everyone.

Up to World War 2, international trade agreements such as FCNs or other joint preferential arrangements were predominantly bilateral. They were negotiated and implemented on a mutual basis and focused on the reduction and/or removal of tariffs and other trade restrictions on trade in goods between the parties. The process was straightforward bargaining, determined by the respective interests and priorities of the parties: “I will take x percentage points off my tariff on product A if you will reduce your tariff on product B by y points.”

At the end of World War 2 farsighted statesmen determined not to repeat the gross economic policy errors of the 1930s. Already in 1944 the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, held at Bretton Woods in the USA, had brought together representatives of 44 countries to discuss a basis for placing the international economy on a more secure and codified basis. This process led to establishment of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

A third and complementary institution was to be an International Trade Organisation (ITO) with supranational powers, which would systematise and enforce agreed principles and rules for the conduct of international trade. Preparatory negotiations began in 1946 leading to the drafting of a document known as the “Havana Charter”, intended for agreement at a conference in Havana in 1947-8. The Charter covered areas rather wider than tariffs and other operational aspects of international trade. It extended inter alia to regulation of international trade finance; control of anti-competitive practices; employment practices; agreements regulating and ensuring the supply of commodities and raw materials; and a requirement for members to maintain a balance between their export and import trade. However it, and with it the proposed ITO, never came into force because ultimately the US Government refused to submit the Charter to the Senate for ratification, knowing that its supranational reach would lead to its being rejected.

Meanwhile in expectation of the establishment of the ITO, on 30 October 1947, the provisions of the Havana Charter which dealt with the processes of international trade were separated out and provisionally applied by 23 founder-countries with effect from 1 January 1948 as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Essentially GATT built on and codified principles which were well established from the history of bilateral trade treaties, including MFN; national treatment; transparency of national legislation and regulation; fair and equitable customs procedures; prohibition of QRs except in specified emergency circumstances; and procedures for investigation and redress in cases of distorting trade practices such as dumping (firms exporting goods at prices lower than charged in their domestic markets) or unfair subsidy of exports by governments. GATT also established a transparent mechanism for settlement of disputes between members. All these provisions related exclusively to trade in goods.

Reducing tariffs

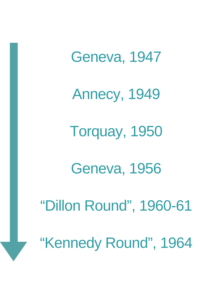

The primary and most urgent task of GATT in those early days was reduction of tariffs and elimination of wartime QRs. GATT established a ratchet-mechanism for tariff reduction, in that a tariff rate, once notified to GATT in a member’s national schedule, was regarded as “bound” and could not be increased above that level without the negotiation of comparable tariff reductions on other products to compensate the countries affected by the increase. GATT conducted the following “rounds” of tariff-reduction negotiations, which really did often involve late-night bargaining sessions in smoke-filled hotel suites:

During these two decades tariffs on goods were unevenly, but significantly, reduced although high tariff rates still persist in areas which governments perceive as “sensitive”, such as agriculture (where protection and distorting subsidies were never effectively tackled by GATT) and textiles. At the same time, GATT’s membership steadily increased and it began to build up substantial jurisprudence through decisions of the members and adjudications by the disputes mechanism. It became clear that the growing complexity of international trade required governing provisions that were more detailed than the basic GATT Articles. It was also clear that the nature of international trade was changing fast, with national systems of trade regulation and product and safety standards assuming more importance in trade regulation than tariff levels and having the potential to act as very effective barriers.

Extending the coverage of trade agreements

In 1973 a further GATT negotiating Round was launched in Tokyo. It took an unprecedented 6 years to complete, in part because the US Administration was paralysed for some years by the Watergate scandal and the fall of President Nixon. Eventually however the Round was concluded, not merely with further tariff reductions, but with the promulgation of six much more detailed Agreements on operational matters which amplified and clarified the working of the relevant Articles of GATT, viz.

- Technical Barriers to Trade (commonly called the “Standards Code”)

- Government Procurement

- Anti-dumping investigations and remedies

- Anti-subsidy (countervailing) investigations and remedies

- Customs Valuation

- Import Licensing Procedures

Three Agreements were reached on specific sectors, namely:

- Bovine meat (to promote liberalisation and expansion of international trade in meat and livestock)

- International Dairy Arrangement (to liberalise and expand trade in dairy products)

- Civil Aircraft (removal of customs duties and similar charges on civil aircraft and parts)

The Tokyo Round also adopted a series of decisions, the most important of which was on Differential and more Favourable Treatment, Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries (the so-called “Enabling Clause”), which permits developing countries to offer to developing countries tariff and other trading concessions that would otherwise contravene the MFN obligation.

From GATT to the WTO

In the Tokyo Round GATT member countries recognised that government regulation of trade procedures, technical standards and access to supervisory systems were at least as important as tariffs in influencing international trade, and needed to be taken fully into account in trade negotiations. Meanwhile globalisation was gathering pace and major international enterprises increasingly shifted from exporting finished goods to investing in manufacturing capacity in markets overseas. Given the growing and in some cases dominant importance of services in their economies, Governments recognised that the GATT system, though it remained essential in the international economy, needed to be radically updated. After long and intense debates, GATT members convened at Punta del Este in Uruguay in September 1986 to launch a new negotiating Round (the so-called “Uruguay Round”).

The chief points of contention were proposals for the full incorporation into the GATT system, for the first time, of agricultural trade and subsidies, and of services, both of which were initially opposed by leading developing countries and by some within the EU. However a compromise was reached which permitted all the proposed issues to be discussed in over a dozen working groups.

Eventually after eight years of tortuous negotiations a comprehensive package of “Uruguay Round Agreements” was signed at Marrakesh in 1994 and came into force on 1 January 1995. This re-established the GATT as a treaty-based body, the World Trade Organisation, which embraced the existing provisions and accumulated jurisprudence of GATT up to 1994 under the rubric of “GATT 1994”, which remains the basic text of the WTO. Within this framework twelve new Agreements on trade in goods were adopted, including updated and much expanded versions of the main Tokyo Round Agreements, and an entirely new Agreement on Agriculture which provided for disciplines on domestic production subsidies and phasing-out of export subsidies.

Also new were the General Agreement on Trade in Services, designed to open up international markets to services investment and trade on the basis of principles of openness and non-discrimination adapted from the GATT; and an agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPs” for short) which imported into WTO system members’ existing obligations under the various international Conventions on patents, trademarks and copyright. Marrakesh introduced a new mechanism for regular review of WTO members’ trade policies, and a much strengthened and more effective dispute settlement system which has been extensively used since its implementation in 1995. During the lifetime of the GATT and the WTO well over 500 disputes have been initiated, though some of these could be settled at the initial stage of consultation and did not need to go to full adjudication.

Growing importance of non-tariff issues

Reduction of tariffs and elimination of other barriers to trade remain a central focus of the WTO. However by now successive tariff reductions, both in multilateral negotiations and on the autonomous decision of individual countries, have reduced the across-the-board average of tariffs in the main developed economies to around 3%, though significant sectoral “peaks” remain in sensitive sectors such as agriculture, textiles and vehicles. In some developing countries tariffs remain an important means of raising revenue. However the Uruguay Round Agreements marked a decisive step in the focus of international trade policy away from the traditional GATT concerns with goods trade towards a much broader recognition of the wider, and often more difficult, issues of the impact of government regulations, safety and health standards, treatment of inward investments, accreditation under systems of prudential regulation, recognition of qualifications, and (increasingly) environmental impacts of trade, labour standards and citizens’ rights.

Reflecting this evolution of emphasis at the multilateral level, FTA and RTA negotiations also now extend to much wider issues of economic and technological cooperation, environmental protection, human and employment rights, gender equality, and provision for redress in the event of abuses.

Where now?

This complex web of issues with which trade negotiators must now grapple has rendered impracticable the traditional GATT/WTO concept of a comprehensive package of agreements balancing differing and often conflicting interests. In November 2001 at Doha the WTO launched a further negotiating Round, or Agenda, with a specific focus on development issues and a deadline for completion of 2005. Seventeen years later that Agenda remains deadlocked, although progress has been made on a few specific issues, including a major Agreement on Trade Facilitation measures. In fact, already in the immediate aftermath of Marrakesh the WTO had launched limited or sectoral subsidiary agreements on matters which the Uruguay Round had not been able to settle satisfactorily, such as telecoms, financial services, spirits tariffs and tariffs on IT equipment. Only members who were directly concerned subscribed to these. Slowly and reluctantly, but inevitably, WTO members have accepted that future progress on trade liberalisation must be incremental, predominantly on a sectoral or topic basis, and where necessary on a limited or plurilateral basis between interested governments acting within the ambit of the WTO.

This was clearly demonstrated by the fact that the WTO 11th Ministerial Conference (MC11) held in Buenos Aires in December 2017 could come up only with a general statement of intention to continue negotiations in all areas. Otherwise the Conference adopted four sectoral or topic agreements for further work, as follows:

- Agreement to continue work on devising comprehensive disciplines on fisheries subsidies to eliminate subsidies that contribute to overcapacity and overfishing, with a view to definitive agreement by end-2019.

- A Work Programme on electronic commerce to reinvigorate work on that topic, to be reported back to the next Session of the Ministerial Conference in 2019.

- Continued work on devising a basis for launching and investigating complaints regarding “non-violation” breaches of Intellectual Property Rights (i.e. which do not entail a specific violation of obligations by the party complained against).

- Continued commitment to the Work Programme on Small Economies, with the aim of identifying concrete measures of assistance to small economies and their integration into the world economy.

At the closing ceremony of MC11 the WTO Director-General did not hide his disappointment at the meagre scale of the results. Nevertheless, even though the day of comprehensive multilateral trade agreements may have passed, the WTO continues to have a vital central role in the collection and dissemination of trade-related information, and as a respected forum for civilised policy debate and settlement of disputes between its 164 member countries.