Stop Crying Your Heart Out – Responding to US Tariff Threats

President Donald Trump signed a new executive order on 13 February 2025 mandating “reciprocal tariffs”. The order has far reaching, and not yet fully understood, consequences for international trade and the trading system. We consider effects and possible responses.

The new executive order on reciprocal tariffs

President Trump’s executive order mandating “reciprocal tariffs” has been met with equal measures of perplexity and consternation. Under the order, the US will set its tariffs at levels reflecting the market access restrictions it finds its partners place on US exporters. Importantly, the order does not confine the US authorities to considering only customs duties imposed by partner countries. The potential trade war front has been broadened to include indirect taxes (notably EU VAT arrangements and digital taxes), exchange rate effects, subsidies, regulatory measures, anti-trust proceedings that “unfairly” affect US businesses, and “any other practice” that limits market access or fair competition with the US’ “market economy”.

The executive order was signed a few days after tariffs of 25% on all steel and aluminium imports had been announced. But observers awaiting clarity as to what US tariffs in general would look like will have been disappointed. If anything the shopping list of concerns increases uncertainty and unpredictability around the size and scope of tariffs. Moreover, the announcements made in parallel that there would be tariffs in some sensitive sectors – cars and pharmaceuticals – “over and above” those envisioned in the executive order highlight the likelihood of discretionary tariff increases.

A signal, not a schedule

It is of course possible that trade nerds within the office of US Trade Representative will spend the next 6 weeks glued to gravity models of trade working out ad valorem equivalents to non-tariff measures, add these to a line by line analysis of tariffs, and come up with proposals most complicated tariff schedule known to humanity. But this is likely to be an exercise in vanity, a chasing after the wind. In any event, setting the US tariff schedule is ultimately the prerogative of Congress, not the president.

A more plausible view is to treat the order as a signalling mechanism, both domestic and internationally. Domestically because government needs to reconcile the pure nativist/ isolationist strand of its electoral base, on one hand, and the more commercially minded strand that wants to leverage opportunities overseas (the contrasts between the two can be seen in the two separate chapters on trade within the Project 2025 manifesto). Internationally, it signals a maximalist approach to trade partners which would involve reworking the architecture of trade rules, and casting access to US market as a bargaining chip to further US interests, commercial and geopolitical. A few points stand out.

First, what is striking is how much of the order refers to things the US can do, and already does, through its various legal frameworks authorising executive action of tariffs. And more pointedly, how much of this can be done within the framework of WTO rules, or the Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) that the US has signed.

But this observation simply underscores the US’ determination to do things unilaterally: it does not want rules-based trade as it thinks it can get a better outcome by leveraging its size on a case-by-case basis. The US has for some time now, regardless of the party in power, been walking away from the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) principle that underpinned the international trading system. The executive order has turbo-charged that trend. More pointedly, by incentivising partners to cut special deals with the US, the order wants these partners to walk away from MFN too, and (short of negotiating a full FTA with the US) operate outside WTO rules. In any event, both the order, and other recent actions, have also torpedoed the network of FTAs that the US has negotiated. In sum, rules-based trade is out, power-based trade is in.

Secondly, reading between the lines, China and the EU are the primary targets. Point 5 of the order, which draws the distinction between the market based economy of the US and others, reprises the language of the last decade regarding action against interventionism in non-market economies (China), and to this can be added references to currency manipulation and mercantilist policies. That the EU is a target is seen in references to regulatory requirements, and VAT, notably. The US’ gripe against the EU VAT regime is a long standing one that never found favour under WTO rules. The US now thinks it can pursue the issue outside the scope of those rules; possibly in order to create negotiating space to implement a border-adjusted corporate income tax proposal that has been circulating in congress and which would be challenged under trade law.

Finally, the specific focus of the executive order is on alleged harmful practices. Industrial policy objectives and national security, which were the motivation for steel and aluminium tariffs, take second stage. For all the talk about tariffs being “beautiful”, the logic here seems to be that if partners keep their barriers low or remove them, the US could do likewise, at least in sectors that are not deemed sensitive. Reciprocal reductions in trade barriers lay at the heart of the post-war trading system. And while the US has walked away from the WTO and its key principles of non-discrimination, the notion of reciprocity holds some scope for negotiated outcomes that can mitigate the risk of new tariffs, if not lower existing ones. The executive order might have opened a particularly nasty trade version of Pandora’s box; but as in the original version of the tale, there may be hope lingering at the bottom.

What is to be done?

Translating hope into reality will take patience and effort. Part of story is internal to the US. In the long run, protectionism will cost the US. Taxes on imports are also taxes on exports. Tariffs will reduce the US’ trade intensity, which will eventually flow through the reduced growth. Moreover, by reneging on its existing WTO and FTA legal commitments, the US undermines the credibility of its future promises of reciprocity. That in turn increases uncertainty, and thus the costs, investors face in doing business with and (importantly), within the US.

But these are longer term effects. They will play out well beyond the political cycle of the current administration. The shorter term effect of tariffs are also ambiguous. The US is a large economy, so tariffs will likely improve its terms of trade, which in turn will boost GDP in aggregate. Some of our recent modelling suggests that on a high tariff scenario (60% on China, 20% on everyone else), that this uplift could be around 0.5%-0.75% in a year. At the same time, tariffs increase prices, which will have a regressive effect on incomes: poorer households will lose out the most.

The domestic and economic and political economy effects of tariffs are ones that the current and future administrations will have to navigate. Despite the longer term negative consequences of tariffs, it is unlikely that we will see a return to liberal attitudes to trade in the near future. Both political parties are dominated by factions reflexively hostile to trade. So the question for other countries is what responses they should take.

Turning the other cheek and sticking together

The impetus for retaliation is understandable, and comes from many sources. Partly this is just a visceral political response. It is also grounded in the logic of international trade rules. If a country is in breach of trade law, then retaliation is permissible once other aspects of resolution are exhausted. But the concept of retaliation only works within a collective action framework when the other party ultimately can be presauded to see values in collective rules. The US clearly does not any longer –the whole point of the executive order is to convey that – and it is thus unlikely that retaliation will generate any change. To the contrary, it may push the US on an even more isolationist stance.

There are, clearly, other ways of retaliating than via tariffs. These could include restrictions on data and digital sectors, preferential procurement, and loosening intellectual property. But these also have very specific costs, and moreover none of these things partners like the EU or the UK would like to see generalised on a global scale as that would harm their interests too.

Overall, fighting fire with fire does not seem to be a wise idea. A few years ago, we modelled the economic impacts on the EU of its approach to strategic autonomy, which covers a range of instruments of the type that could be used to retaliate against. We found that these measures could cost the bloc in net terms, anywhere between 0.2% and 0.6% of real GDP, which is within the range of plausible effects generated by US tariffs in the first place. That’s excluding the possibility that retaliation begets further retaliation.

It would also be problematic if partners tried to cut side deals with the US. The executive order clearly seeks to incentivise this by offering reciprocity on a country-specific basis. This pays because not only could a country avoid tariffs, it would stand to benefit from preferential access if US tariffs fell on similar goods exported by other countries. This can be seen in our modelling of how a scenario in which the EU gets hit by a 20% tariff, and the UK does not, plays out: the UK gets a substantial boost in trade.

But the allure of such opportunistic gains is problematic from a bargaining point of view, given the US’ intention is clearly to pick partners off one-by-one to strengthen leverage. Partners – at least relatively similar ones such as the UK and the EU – are better off sticking together. This is a dynamic game, and nothing in the US’ approach suggest that a side deal will be respected on an ongoing basis. Moreover, it isn’t possible within trade rules to cut a specific deal with the US on tariffs on a few product lines. That would violate the MFN principle at the heart of trade rules. The US may have walked away from that; it isn’t in the interests of partners to follow suit since they themselves will suffer from a further fragmentation of the trading system.

Fragmentation will also increase if the US’ trade partners cede to the temptation to raise tariffs on other countries to counter trade diversion effects of US protectionism. Politically this is difficult to avoid, but economically it can be in their self-interest to resist. One of the subtle effects of US tariffs is that because it is a large economy, a drop its demand for imports reduces world prices. Countries that are net importers of goods like the UK gain from this, and the price reducing effect can mitigate some of the economic hit from lost exports. Raising duties on imports via trade remedies, for example, can act against this mitigation.

Go the extra mile

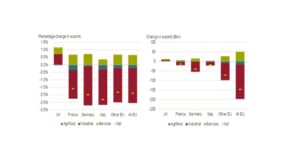

Tariffs are a subset of trade costs, and they affect a subset of trade. There are several implications of this. The first, as our graphs show, is that US tariffs penalise goods, but can shift relative trade costs in favour of services exports, which encourages their growth (and this is after we control for any reduction in services that are embedded in goods). Clearly, enabling the policy framework for services trade will help countries like the UK and EU member states withstand tariff shocks.

This is also one further reason why retaliation is a bad idea: most retaliatory measures will bias relative prices against services and/ or increase the trade costs faced by services, in addition to worsening the anti-export bias against goods. Developing countries in particular would do well to cut their tariffs and reduce the trade costs they have been imposing on themselves.

The second implication is that if US tariffs place upward pressure on trade costs, it pays to look at other ways of reducing trade costs, many of which are home-grown. Services like logistics, connectivity and transport have a key role to play here: they account for around 50% of trade costs according to the WTO. Inward liberalisation would help bring these down. Cooperation on reducing the costs to trade induced by regulation is another element. A third would be facilitating customs processes and checks.

The UK and the EU are obvious examples where there are quick gains to be achieved though bilateral cooperation on these matters. Within the EU single market itself, there remains a significant unfinished agenda in addressing regulatory measures that hamper integration and the ability of businesses and industries to grow by taking advantage of the scale of the single market.

Much of this action on trade cost can be undertaken within the existing framework of trade rules and institutions. That is one reason also why it pays for countries on the receiving end of tariff threats to work together, rather than seeking to get one over the other by cutting special deals, and to avoid entering a cycle of retaliation. Moreover, these efforts could also address some of the concerns the US has expressed, such as burdensome regulations in services and tech sectors. They may offer a route towards a reciprocal lowering of trade barriers and rekindling US interests in being at the global negotiating table. Going the extra mile on trade costs – in effect reducing the “distance” between economies – is therefore worthwhile in tariff-prone times.

In sum, the new trends in trade policy in the US herald a less certain, more fragile era with a potential for significant damage. But there also reasons to reject the counsel of despair, and to recognise that there are concrete measures that can be taken to secure an open trading system.