The Other “No Deal”: Brexit and FTAs with non-EU countries

Political debate in the UK has been dominated in the last few months by the issue of the “Irish Backstop”. Division over the issue has prevented parliamentary ratification of the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated by the UK Government and the EU. The impact of the UK leaving the EU on a “no deal” basis – i.e. without either any agreement on the terms of its departure, or on a framework for negotiating a future relationship – is well documented.

But “Brexit” is not only about the UK’s posture towards the EU. The UK’s relationships with countries outside the EU also stand to change. This is partly because the UK, by virtue of its EU membership, is currently a party to 40 or so Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) that the EU has signed. On leaving the EU, the UK runs the risk of reverting to trade with these partners on Most Favoured Nation terms, rather than the more expansive preferential terms contained in the FTA. That is, unless the UK can negotiate its own FTAs with these partners.

What is the problem?

As part of its common commercial policy, the EU has negotiated FTAs on behalf of its member states with various partners. These partners vary in location and economic size. Significant ones include Canada, Korea, Singapore, the EFTA countries (Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Lichtenstein), and most recently Japan. Some are also countries with which the UK has long-standing political relationships, such as the CARIFORUM countries (see here for an analysis of Brexit issues from their perspective).

The UK is a WTO member in its own right. But it is a party to these FTAs only as long as it is a member of the European Union. Recognising this, the UK government stated its intention to negotiate replacement agreements. This is known in the jargon as “bilateralising” the EU FTAs. But so far there has been little progress to be seen, apart from a deal with Israel and an agreement with Switzerland mainly covering the residency rights of citizens and travel rights. The UK thus risks crashing out of these arrangements at the same time as it leaves the EU, accentuating the potential impacts on trade of Brexit itself.

How does the withdrawal agreement affect all this? Under the current terms of the withdrawal agreement, the UK would remain part of the EU’s common customs rules until the end of the transition period (end-December 2020, with a possibility of extension); or for as long as the backstop solution for Ireland remains in place. This means that the UK would still implement the EU’s common external tariff, including preferential tariffs to free trade partners.

But this does not guarantee market access in FTA partners such as Canada, Japan or Korea. A footnote under Article 129 of the Withdrawal Agreement states that the EU will notify countries with which the EU has signed FTAs, that these countries should treat the UK “as a Member State” during the transition period. But it is far from clear that this creates any obligation for these countries to treat the UK in such a way. They may, out of benevolence. But equally, they may be minded to pocket the market access they will continue to have to the UK during the transition period, and wait until there is further clarity on the future status of the UK’s relationship with the EU to then negotiate new arrangements with the UK.

What if the UK crashes out of the EU without a Withdrawal Agreement? The UK would lose the preferential access negotiated by the EU with FTA partners. But now these partners would also lose any preferential access to the UK. Leaving the EU without the withdrawal agreement may strengthen the incentives countries such as Canada, Japan, Singapore and Korea have to rolling over current arrangements in order to preserve continuity of access. Viewed in these narrow terms, a “no deal” exit could strengthen the UK’s bargaining position vis a vis non-EU FTA partners. But that needs to be set against the likelihood that the UK’s position completely outside the EU could weaken the UK’s bargaining position because: (i) the adverse economic impact of a no-deal exit might make it more desperate to sign agreements with non-EU partners (ii) the UK outside the EU is a less valuable proposition to trade partners and investor based in them, who won’t be able to take advantage of cross-border supply chains.

How big is the problem ?

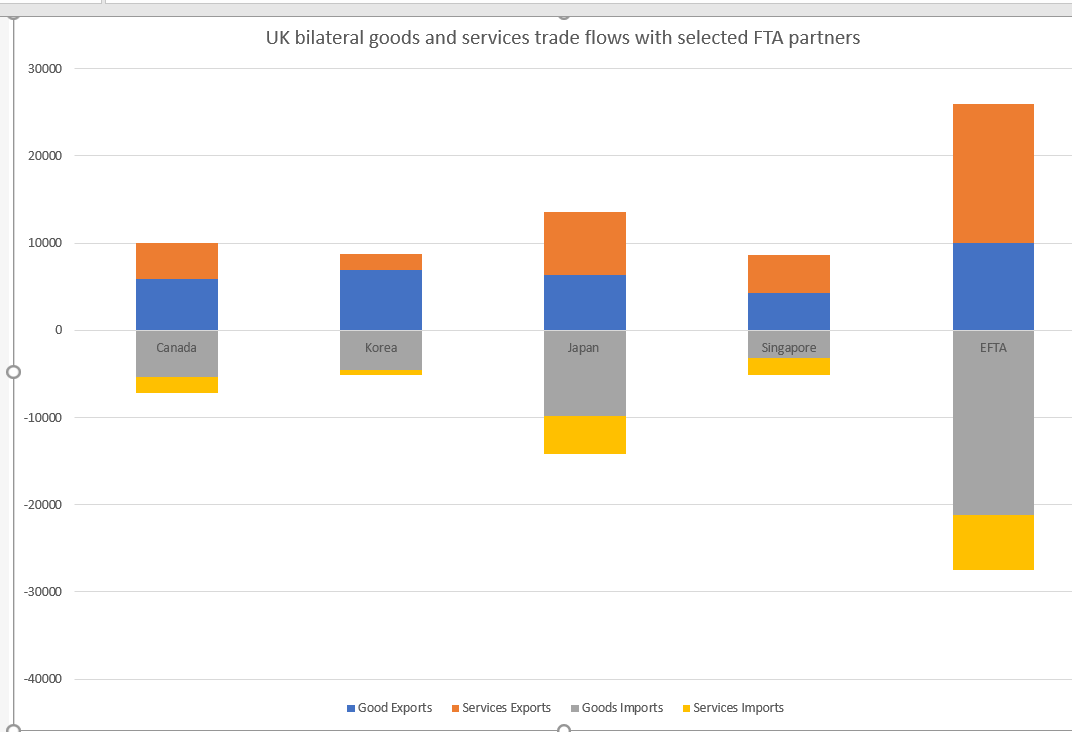

The chart below presents the UK’s bilateral trade balances with some of its principal partners with which the UK has a FTA by virtue of its membership of the EU. Collectively these countries account for around 10% of current UK goods exports and 20% of current services exports.

Exiting FTAs can have significant effects on bilateral goods trade, with research pointing to effects of up to around 24% on average.

But the exact magnitude of these effects will be determined by the structure of trade and the trade partner. Average applied MFN tariffs – those that would apply outside a FTA – are generally low in the partners referred to above. This mitigates some of the no-deal risks for the UK. But some sectors have a greater level of MFN protection, both through tariffs and non-tariff measures. These are ones in which having a FTA can give an advantage, and, conversely, leaving a FTA can generate considerable costs.

What are the possible flashpoints? Let’s begin with goods.

UK exports to South Korea have more than doubled in nominal terms since the application (provisional at first) of the EU-Korea FTA in 2011. The main exports are petroleum, machinery (including general machinery, optical and precision instruments), and transport equipment (mainly automotives). Pharmaceuticals account for a smaller but substantial share. Beverages are small but important niche market (e.g. Whiskeys) Applied MFN duties on cars are 8%, at around 6% on average for machinery, around 4.6% for pharmaceuticals (8% for medicaments), and just over 6% for optical and other precision manufactures. The MFN applied tariff on Petroleum, exports of which grew rapidly since 2011, is 3%. On beverages, the average is just under 19% (rising to 30% for Beer and 20% for Whiskey).

Switzerland accounts for around two-thirds of the UK’s EFTA exports. Trade in industrial goods is covered by a free-trade agreement between Switzerland and the EU that entered into force in 1972. Major UK export sectors that could be exposed to shocks are machinery (including precision and electrical), vehicles, and miscellaneous manufactures. The complicating factor with Switzerland is the opacity of its duty regime in these sectors, which rely on specific rather than ad valorem duties. Duties on cars for example are between 12 and 15 francs per 100 kg gross weight.

In Canada, motor vehicles are a potential issue (with average duties of 6%). But otherwise Canada offers a largely liberal environment which the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) it signed has done little to enhance in products of export interest to the UK. (which is somewhat ironic given the extent to which the “Canada model” has dominated aspects of Brexit discourse). Japan (in non-agricultural goods), and Singapore, also present liberal tariff environments.

In the case of Japan (and also South Korea) a significant set of access issues relate to non-tariff measures, and specifically the costs imposed on exporters by divergent regulations and methods for conformity assessment. The motor industry in the UK made various representations to the government as the negotiations took place. Because the EU-Japan FTA only recently entered into force, the effects on NTMs are difficult to assess, though the European Commission observed that Japan had made progress in aligning its standards in areas such as motor vehicles to international ones. For South Korea, the EC’s technical analysis found modest reductions in non-tariff measures applying to motor vehicles (ad valorem equivalents of just under 3%) and more significant ones for electrical equipment (9%). Importantly, the FTAs set up mechanisms for on-going cooperation on regulatory matters that the UK will no longer be able to access.

Finally, moving away from focusing purely on exports, if the UK were to revert to applying the MFN tariffs it has inherited from the EU, this would affect trade partners, but also itself to the extent that these imports are used in supply chains that involve the UK. This is notably the case in the automotive sector, and the availability of parts.

And what about services?

The effects of standard FTAs on services are on average much weaker than in goods. Estimated impacts are in the order of 4-5%. The reason is that FTAs tend to reduce the gap between bound commitments under the WTO agreement on services (the GATS), on one hand, and applied levels of liberalisation, rather than spur additional liberalisation on the ground. Switzerland, for example, accounts for around 40% of the UK services exports to all the countries referred to in chart 1, yet there is no services FTA currently linking the UK to Switzerland.

Having said that, UK services exports to South Korea nearly doubled since the entry into force of the FTA. (The EU found that on average EU services exports increased by 50%). While it is obviously difficult to establish causation, it is worth noting that two-thirds of respondents to a survey by EU services industries found that the FTA was highly effective in increasing their exports to South Korea. The EC’s analysis also found a significant reduction in non-tariff measures affecting financial services.

So what is to be done?

The prospects of a no-deal with its non-EU trade partners is therefore a significant issue for the UK. It is moderated by the fact that the UK’s main non-EU trade partners have relatively liberal MFN regimes. But several sectors stand to be exposed. Aside from the value of trade at risk, the sectoral concentration could have geographic distributional impacts. Areas that specialise in services (such as London) and have therefore depended only to a limited extent on these FTAs for expanded trade opportunities, stand less to lose than those that specialise in manufacturing and other industrial goods trade. Ironically, these are regions that tend to have voted in favour of leaving the EU.

The prospects for the UK to “bilateralise” its arrangements with trade partners are constrained in part by the fact that the incentives for these partners to reach a quick agreement are clouded by the uncertainty surrounding the UK’s future relationship to the EU (which is economically, and indeed politically, of greater importance to these partners); and also by the properties of the withdrawal agreement currently on the table, which seems to offer the trade partners the possibility of pocketing access to the UK “for free”.

Given that trade partners have an interest in an orderly exit, and that an orderly exit will almost inevitably involve a transition period in which the UK implements the EU’s common external tariff, it might be in the interests of trade partners to seek to roll over the UK’s current access to their markets, as a sort of down-payment to reward the UK for an orderly exit.

In the longer term though, it is difficult to get around the fact that the UK outside the EU is a less attractive prospect for the UK’s non-EU trade partners. Consequently, sustaining the UK’s current level of access to these partners may require the UK to go beyond actual levels of liberalisation. It should therefore identify those areas in which it would be prepared to liberalise more, drawing on the knowledge that one’s own liberalisation has as big if not bigger effects on one’s economic growth prospects than the liberalisation of partners.

This will require considerable resources, and it is far from clear how well resourced the UK currently is in terms of its negotiating and analytical capacity. Most of the government’s resources appear to be mobilized to support negotiations with the EU and the steps needed to if the UK were to leave on a “no-deal” basis. It also means that ambitions of striking new agreements with other new trade partners (such as the US, China, or India) will need to be put in abeyance.

Finally, it is useful to recall that one of the main arguments floated in favour of leaving the EU was that the latter was slow at agreeing FTAs with the rest of the world. While there is certainly a strong argument that the EU could have been, and ought to be, more ambitious, this analysis reveals that one of the immediate impacts of leaving is the loss of access to the liberalisation the EU has achieved on the UK’s behalf. And that the UK will be have its work cut out simply running to stand still.