Immigration was one of the key issues of contention in the referendum of 23 June 2016. The desire to limit immigration for the European Union was cited as one of the main factors, if not the main one, motivating the leave vote that prevailed on the day. Since then, the Government has listed the control of immigration as one its priorities for future negotiations with the EU. The commitment should be read in the light of previous commitments to reduce annual net migration to 100,000 or lower. The desire to control immigration is so pronounced that the government has in essence accepted to leave the single market for services if it can be allowed to withdraw from single market commitments on the movement of labour. That position is reflected in the Withdrawal Agreement and in the Political Declaration agreed with the European Union in late 2018. The magnitude of this qui pro quo can be seen by considering that services account for close to 80% of UK GDP and are the fastest growing part of the UK’s exports. Clearly the government believes that the political gains from restricting immigration are worth the economic costs. But why? And is this line of reasoning tenable?

That the politics of immigration are emotive and volatile cannot be denied. The challenge for economists is therefore to present evidence that can guide the debate, and ensure that decisions taken at the political level are consistent with the public good. The purpose of this article is therefore to consider the evidence on immigration from the EU and its impacts on the UK, and suggest some implications for policy. We focus closely on the interaction between immigration, labour markets and skills, since this interaction is a primary mechanism through which the overall welfare and distributional impacts of immigration are mediated.

The UK and EU immigration

Article 45 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union establishes the right of all citizens of the European Union to “move and freely reside” within the territory of Member States. Article 46 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits discrimination between workers of member states in matters of employment.

Around 3.2 million people living in the UK in 2015 were citizens of another EU country, which is close to 5% of the population. And, about 2.2 million EU nationals (non-UK) are in work, which is about 7% of people in work. Over half the EU nationals in the UK today came in to the UK since 2006. EU nationals of working age are more likely to be in work than UK nationals and non-EU citizens. About 78% of working age EU citizens in the UK are in work, compared to around 74%. Figures for 2015 suggest that 1.2 million people born in the UK live in other EU countries.

In considering the impacts of migration, we need to consider the mechanisms through which the effects of immigration play out:

- Impacts on employment and wages depend on the extent to which migrant labour is complementary to, or substitutable for, indigenous labour. Where there are effects of complementarity, wages and/ or employment will rise, whereas substitutability may lead to displacement or a fall in wages. If migrant labour is relatively low-skilled and complementary to high-skilled labour, we may expect the productivity of the latter to rise, and wages accordingly. There may be a negative effect on low skilled earners.

- Immigrant labour may stimulate structural changes in an economy. For example, an influx of skilled workers may increase the return to investment in capital and technology (that are complementary to these skills) leading to an expansion of sectors that use these inputs intensively. Changes in the level and composition of demand for goods and services may cause some sectors to expand (increasing the return to capital and labour in these sectors) and others to contract.

- Immigration may stimulate trade, by reducing trade-related transactions costs (e.g. through networks or through knowledge of local markets, preferences, and institutions).

- Immigration is likely to generate multiple fiscal impacts, reflecting both fiscal contributions made by immigrant labour, and transfers in the forms of benefits.

What does the evidence suggest has been the impact, on balance, for the UK?

On wages, the empirical evidence from a number of studies suggests no overall impact on wages. Across different wage classes, the evidence suggests some gains for middle and higher wage earners, and small losses for lower wage earners. But the impacts are hard to disentangle from other significant trends, notably the influence of technology and trade. On the latter, sectors and regions that are more open to trade have tended experience a greater increase in real wages.[1]

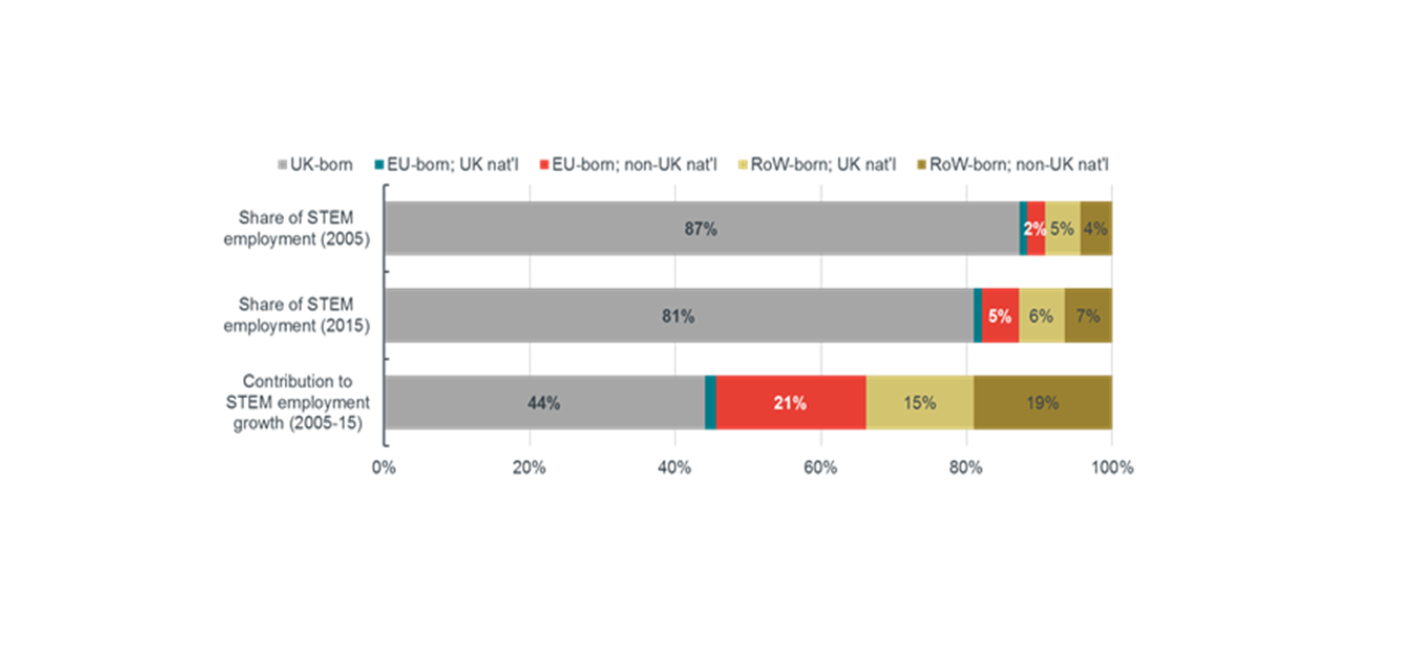

In the area of skills, Frontier’s research shows that migrants have made important contributions to sectors that rely on science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workers. Over half the employment growth seen in STEM occupations in the last 10 years has been migrants (and half of those were from the EU). This accords with evidence from Germany and the US. We shall consider the STEM sectors in greater detail in the next section as they provide an example of the close interplay between immigration, labour markets, skills and other policy issues (notably trade and the operation of supply chains).

The issue of skills spans both private and public sectors. Nearly 60,000 out of the 1.2 million staff (or 5%) in the English NHS are citizens of other EU countries. The proportion of EU staff can be significantly greater in certain grades: 13.2% of speciality doctors and 18.3% percent of staff grade workers are EU nationals[2]

The influx of immigrants also appears to have had a positive impact on the UK’s trade. An econometric analysis estimated that a 10% increase in immigration from non-commonwealth countries is estimated to increase long-run exports by 5%. The effect for non-commonwealth countries is much stronger than for commonwealth countries, and reflects in part the impact of immigrants from Europe.[3] The findings on the export response to immigration is consistent with findings for Spain[4], the US[5] and Canada[6].

On the fiscal side, European immigrants have paid more in taxes than they received in benefits or imposed in costs on public services ,– according to research by the UCL Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM). European immigrants who arrived in the UK since 2000 contributed more than £20bn to UK public finances between 2001 and 2011. Over the period from 2001 to 2011, European immigrants from the EU-15 countries contributed 64% more in taxes than they received in benefits. Immigrants from the Central and East European ‘accession’ countries (the ‘A10’) contributed 12% more than they received. Revealingly, if we consider the ratio of revenues generated to expenditures incurred for EEA immigrant cohorts since 2000, we find that ratio consistently exceeds the ratio for indigenous workers. This suggests that EEA immigration has helped reduce the fiscal burden for native populations and also helped to reduce the UK’s fiscal deficit.[7]

A closer look at STEM

We focus on STEM sector given because the government has identified this as crucial for the future of the UK. This is because of the direct contribution of the STEM to social wellbeing, and because of their indirect the links between these sectors and productivity growth (and through that, income). Moreover, employment in STEM occupations grew 17 per cent over the 10 years between 2005 and 2015 versus 6 per cent for non-STEM. While UK –born workers still account for the majority of STEM employment, the main sources of employment growth since 2005 (see figure 1 below).

Figure 1 Sources of STEM employment and growth in employment 2005-2015

The evidence suggests that the UK has had difficulty in getting sufficient UK nationals of the quality required to work in some these key sectors. Evidence from the Employer Skills Surveys suggests that 43% of vacancies for professionals working in science, research, engineering and technology are hard to fill due to skill shortages – this is almost twice the average for all occupations.

If we consider higher education specifically, we observe that 16.4% of staff across all disciplines are EU nationals, and that this figure rises to over 22% for the sciences. The interdependencies with the EU are further strengthened by the magnitude of EU funding flows attracted by UK universities. As a share of total research funding, EU sources have therefore grown from about 8-10% in the period 1994-95 to 2009-10, to 14-16% today. The UK receives around 1.6 times the money it contributes to EU education funding budgets.

In sum, the evidence suggests that the UK has benefitted significantly and in a number of distinct ways from immigration, and this is in keeping with theoretical predictions and the experience of other jurisdictions. This has implications for policy post-Brexit. Clearly, restrictions on immigration are likely to induce costs by constraining the various channels through which immigration has benefitted the UK.

A fortiori, if the UK were no longer to guarantee the rights of EU citizens inducing an exodus of such citizens, the effects are likely to be amplified. In economic terms, this would amount to a stock effect. Stock effects have greater impacts than flow effects. To use an analogy with financial economics, restrictions on future immigration flows would amount to taxing a class of financial assets in a portfolio, while requiring EU citizens to leave would be equivalent to declaring a whole class of assets unviable.

If it is all so good, why are people so upset?

The dissonance between the evidence presented above and public attitudes towards immigration is substantial, and thus warrants further investigation. The first line of inquiry would be to examine the distribution of benefits. It is possible that immigration is beneficial overall, but that though substantial, they are diffuse. Meanwhile, the costs of immigration could be concentrated. For example:

- The evidence reported above on wages points to negative impacts on some low wage earners. Coupled with other factors that put downward pressure on wages, such as exposure to low-skilled workers overseas via trade flows, this could drive hostile attitudes towards immigration.

- Notwithstanding the fiscal contributions of immigrants to social services and their direct contributions through their labour, immigration is likely to create pressure on services in under-resourced areas. While funds can be redirected, there is usually a lag between detection and re-direction, and a further lag before re-direction leads to practical effects

The reasoning here is analogous to that found in trade policy to explain why governments may favour protectionism even if it is a sub-optimal policy. In trade policy, the usual response is to create liberalising coalitions between consumers of imports and exporters to over-ride protectionist constituencies. In principle, the interplay between the four freedoms (goods, services, labour and capital) should create the conditions for a similar bargain as far as immigration is concerned. Clearly, while this might have held for the first two decades of the single market, the leave vote is an indication that this bargain has been eroded (something not confined to the UK).

In addition to the concerns enumerated above, it is possible that immigration is seen as weakening social cohesion and affecting other intangible public goods, such as cultural goods. If that is the case, and the costs are not quantified, it is possible that the calculus of costs and benefits is skewed towards the latter. There is some evidence that values other than economic ones carried the leave vote, specifically personal preferences for order, tradition and security over openness.[1] Immigration can be conceived of as eroding these values.

However, even if that is the perception, it is not clear why objectively this would be the case. There is no objective evidence that immigration has raised the incidence of crime. It is also difficult to see how cultural values are eroded by immigration. Indeed, some of the UKs primary cultural goods – from the creative industries to sport – appear to thrive on access to EU talent. If we consider traditional forms of religion as another example of cultural goods valued by indigenous groups, again there is very little evidence that immigration has had an adverse impact. Indeed, there is evidence to the contrary, if one considers the Church of England specifically[2]; and in any event, the pronouncements of the Church’s leadership support a favourable attitude towards immigration.[3]

What is to be done?

As already observed, the government has set “control of immigration” as one of its priorities for its negotiations with the EU. The reason it is important to sift through the evidence on immigration as well the motivations behind public perceptions and hostility toward immigration is that it helps to answer the question “control to what end?” The objective of controlling immigration purely based on economic evidence about the extent and distribution of costs and benefits, has different policy implications to a scenario in which the objective involves accommodating public preferences, that may be lacking in factual grounding or are based on prejudice. In such a scenario, the policy burden lies in balancing objectives that pull policy in opposite directions and that are qualitatively different.

In such circumstances, the starting point for sound policy is to invoke the Tinbergen principle and to ensure that are at least the same number of instruments as there are targets. Specifically, such an approach could involve the following elements.

First, dealing with the threat of “stock effects” i.e. a significant departure of current immigrants, which would involve considerable economic disruption. This would require an early agreement to safeguard the rights of existing EU migrants in the UK (and vice versa).

Secondly, the question of access to future skills could be, in part at least, addressed through reciprocal commitments made between the UK and EU under a future trade arrangement. In particular the architecture of services trade agreements could be used to this end: specifically, commitments in relation to supply of services via the movement of natural persons, and the ability of firms establishing a commercial presence to bring employees with them. The advantage of this is it would address the question of access to skills via the movement of labour through the prism of trade commitments that are targeted to specific sectoral needs, rather than broader commitments under immigration law. Trade law also recognises the use of concepts (such as safeguards, and economic needs tests) that could be used as “safety valves.” This approach assumes that the UK and the EU would be able to negotiate a trade agreement of unprecedented depth and coverage (outside the EEA).

A third set of instruments would be to ensure that policies that mitigate the distributional impacts of immigration are put in place, specifically in areas such as access to health care, education, and housing. Clearly, each of these are far-reaching policy areas in their own right, but it is necessary to highlight them to illustrate why immigration policy alone cannot carry the sole weight of addressing the immigration policy challenge.

A fourth set of instruments would like in initiatives to better explain the objective benefits of immigration. Considerable attention has been paid in the aftermath of both the Leave referendum and the American presidential election on the way in which facts are communicated and understood by varying groups of people. Initiatives would need to draw on insights from behavioural psychology.

The policy configuration is unlikely to satisfy those who remain firmly wedded to the notion that the government must meet a set quantitative immigration reduction target. The costs of meeting such a target make it an undesirable objective. But given the tension between what should be a policy objective based on the hard evidence, on one hand, and public preferences that lack such grounding, on the other, the suggested configuration may provide a route through which these preferences may be accommodated to a degree, while limiting the harm caused in an objective, economic sense.

[1] Eric Kaufmann (2016), “Its NOT the Economy Stupid: Brexit as a story of personal values”, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/personal-values-brexit-vote/

[2] The Church of England: Resurrection? The Economist, 9 January 2016. http://www.economist.com/news/britain/21685473-parts-established-church-are-learning-their-immigrant-brethren-resurrection

[3] Justin Welby will vote to remain in the EU, The Telegraph, 12 June 2016

[1] Ref Frontier work

[2] NHS Digital workforce statistics for 2016

[3] S. Girma and Z.Yu, (2002) “The link between immigration and trade: Evidence from the UK”, Centre for Research on Globalisation and Labour Markets, Research Paper 2000/23.

[4] Giovanni Peri and Francisco Requena, “The trade creation effect of immigrants: Evidence from the remarkable case of Spain”, NBER working paper 15625;

[5] David Gould (1994), “Immigrant links to the home country: Empirical implications for U.S. bilateral trade flows”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 76, No.2, pp302-316

[6] Head, Keith, and John Ries (1998) “Immigration and trade creation: econometric evidence from Canada,”Canadian Journal of Economics, 31(1), 47—62

[7] Christiano Dustmann and Tommaso Frattini (2014), “The fiscal effects of immigration into the UK”, The Economic Journal, Vol 124, pp593-643.