Trade Policy Lessons from Covid 19

The Covid 19 pandemic has had a severe impact on international trade . The WTO recently projected that global trade could fall in real terms by upto 20% in 2020. A modest recovery could take place in 2021, but this is heavily dependent on the future course of Covid 19, measures taken in response, and trade policy developments.

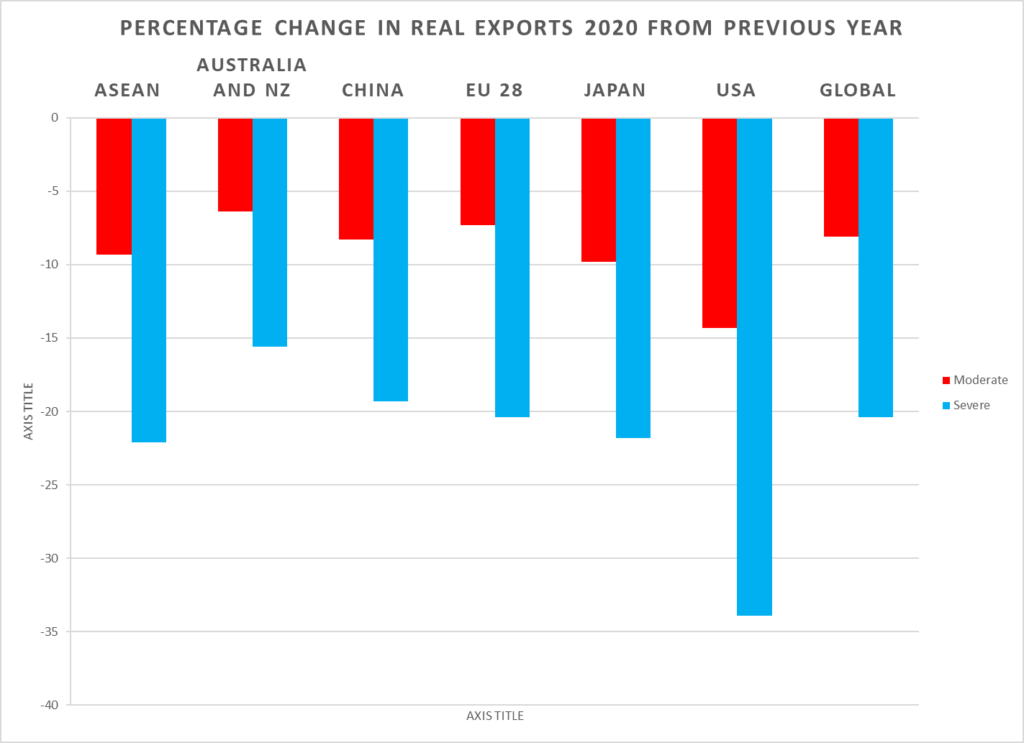

Figure 1, based on WTO modelling, shows reductions in exports for selected countries and globally under a projected moderate impact scenario (red) and severe impact scenario (blue).

The main factors behind the collapse of trade are the same as those that have caused a general collapse in economic activity, namely:

- Disruptions to production caused by the effects of the virus on health, which have had transnational effects in sectors that have heavily globalised value chains.

- Disruptions caused by containment measures, such as confinement, social distancing and border measures, including restrictions on air travel.

- Disruptions caused by (largely ill conceived) trade restrictions on a range of products, from medical equipment and medicines, to food.

- Diminished business expectations (Keynes’ “animal spirits”) and the investment deterring effects of prolonged uncertainty.

The relationship between trade and GDP means that these factors have second and third round effects. For example, sickness and containment measures reduce GDP growth, which in turn has a negative effect on trade. Slower trade further reduces GDP, and these effects are exacerbated by restrictive trade policies.

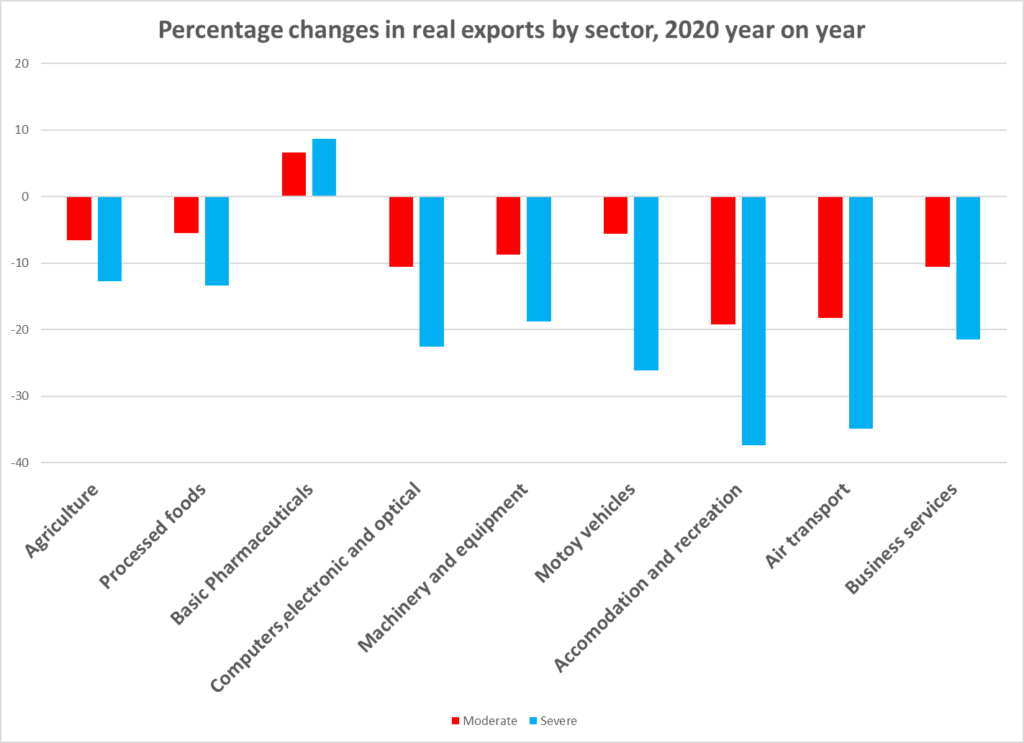

Effects are particularly pronounced in durable manufacturing sectors that have globalised value chains, such as computers and electronics, machinery and motor vehicles. On the supply side social distancing and travel restrictions disrupt the organisation of production, while on the demand side falling GDP and disposable income cause a reallocation of spending away from these. A similar story can be told for services such as travel, transport and business services (See Figure 2 below).

This shock to international trade and its governance comes at a time when both were already fragile. Trade growth in 2019 had slowed markedly, while trade-restrictiveness measures spiked to record highs. Moreover, the Covid -19 episode has raised a number of systemic questions about trade and the governance of trade. Chief among these is the question of resilience: can we build an international trading system in which a shock or failure originating in one part (China, in this instance) can be mitigated, not propagated and amplified. The resilience issue is all the more pertinent given the range of other shocks, notably climatic ones, to which we are likely to become increasingly exposed.

The challenges to trade policy are unprecedented. Meeting it will require a mix of renewed commitment to existing principles of trade, and new thinking about how to respond to the systemic issues the crisis has thrown up. On the latter front, the key question is how to build resilience in trade that does not lead to a drift into protectionism and the economic costs associated with this.

Short term: first, do no harm

As observed above, the short term prospects for the global economy and for trade are bleak. If anything, the WTO projections are optimistic. The moderate scenario assumes an abatement of Covid 19 within three months and a phase out of prevention measures. That seems unlikely now.

The severe case foresees restrictions, mainly in the form of social distancing, lasting up to a year. That also seems optimistic. The risks could be amplified if governments succumb to the temptation of lifting containment policies prematurely, on the false notion that they can trade off a little bit of health risk for a little bit of growth. It is a false notion because the non-linear properties of epidemics and limited knowledge of the virus mean that governments cannot fine-tune.[1] That in all likelihood would lead to a stop-start cycle in which restrictions are lifted, only to be re-imposed when things get out of hand. In turn further clouding investor expectations, investment and hence growth, and dragging out the pandemic.

In those circumstances, the old medical adage “first, do no harm” comes into play. In trade policy terms, that means not giving into the lure of protectionism that inevitably amplifies during an economic downturn. Regrettably, this has already happened to some extent, with a proliferation of trade measures, notably export controls on items ranging from medical equipment to food. Revealingly, a number of countries that have implemented export restrictions have also implemented import liberalisation measures on medical equipment, precisely because they know that trade restrictions are costly. Any single country might calculate that this combination of import liberalisation and export restrictions is a clever policy for itself. It is just that if everybody gravitates towards export restrictions, any benefit from import liberalisation is lost and everyone is worse off.

That sort of adverse outcome is precisely why the multilateral trading system was established at the end of the second world war. Rather than engaging in self-interested behaviour that leads to globally suboptimal outcomes, a better solution would be to agree a reciprocal moratorium on restrictions and then to find ways of addressing the key problem (the availability of medical equipment) at source.

Doing so would is likely to involve a combination of instruments. Clearly, cutting remaining tariffs is desirable: the WTO reports that tariffs on protective gear average around 11%, with peaks of close to 27%, with higher tariffs usually applicable in poorer countries. But beyond tariffs, stimulating supply would likely require subsidies and the acquisition of technology. Both involve navigating trade rules. Subsidies would necessarily be specific and hence under the scope of WTO disciplines. Legal cover could be found in the form of GATT Article XX which allows countries to take measures to secure public health. Moreover, given that many countries have rescinded trade remedy investigations on medical and relate products, revealed preferences suggest that countries should not take action against measures that increase availability.

The question of access to technology requires navigating intellectual property rights. Again, WTO rules on intellectual property, notably on compulsory licensing in the case of national emergency (TRIPS Article 31b) can provide the legal cover needed.

The policy toolkit will need to address the fact that trade in key items is relatively concentrated: according to the WTO, five countries (China, the USA, Germany, Japan and France) account for around half of world exports of protective gear. While four countries (the United States, Singapore, the Netherlands and China) account for close to half of respirators. Production is organised through global value chains, which means that shocks in any part of the value chain (say China) will ripple through globally, and the degree of concentration amplifies impacts. This in turn points to a longer term challenge for international trade and the global economy: that of building resilience.

The longer term challenge of trade and resilience

Over the past two decades one of the key drivers of international trade has been the growth of global value chains, through a combination of technological developments and policy liberalisation. This has increased the efficiency of production by allowing different segments in different countries to specialise in specific tasks.

But it has also arguably come at the expense of resilience. This is because in value chains of increasing complexity and length, a shock in one “node” (a country, or, as in the case of Hubei, a region within a country) can cause widespread damage. That damage will be amplified the more value chains tend to be concentrated – as they are- around a relatively narrow range of countries. The outbreak of Covid-19 highlighted the reliance of global value chains on China. Of the world’s top 500 companies, 300 had facilities in Wuhan. Globally, sectors that are affected include, as already observed, much of manufacturing of durable goods and of medical supplies.

Resilience is the ability to adapt to and recover from shocks. In this case, it would mean value chains that are less prone to disruption because they are less dependent on a particular “node”. Covid- 19 has emphasised the importance of resilience. But the issue will arise in connection to climatic shocks, that are expected to become more prevalent by the middle of the century. And there is also the possibility of cascading technological failure, whether through accident or deliberate action.

To some extent, building resilience in value chains may emerge simply out of the self-interested behaviour of businesses. Having seen how over-reliance on one particular area or country can compromise operations, businesses might deem it prudent to diversify operations, reduce the length of supply chains and build redundancy. In other words, resilience dovetails with efficiency once the risks are properly assessed, and once the option value of things like spare capacity are factored in.

Resilience is already on the radar screen of business. Its prominence in business planning is likely to increase in the wake if the Covid 19 pandemic. But relying solely on the self-interested action of businesses may not suffice. The pressures for profitability over the short term is likely to skew incentives towards suboptimal levels of resilience. Policy interventions are likely to be needed.

What may these be? The one most likely to be considered by governments are requirements that a proportion of production be carried out locally as a condition for supplying markets and/ or subsidies contingent on that.

While such ideas have popular resonance, they have multiple disadvantages. Using trade instruments to localise production is simply a larger-scale variant of the current scramble for controlling flows of medical gear and protective equipment. If generalised, it would increase supply costs globally, with particular bad impacts on countries too small to barter domestic market access for localised production.

Such approaches would likely fall foul of trade rules. Rewriting trade rules to allow them would likely open a can of worms with countries identifying various strategic industries that would qualify for this sort of treatment, leading to a costly escalation in protectionism. If countries really do want to go down this route, better that they be required to justify the choice under exceptions provided for in existing rules to allow the pursuit of health and other public interest priorities.

Rather than using trade measures to localise production, it would be more useful to focus on the core issue: maintaining resilience by building in redundancy and diversification into production chains. The key issue is that the public value of resilience investments is likely to exceed its private value to the investor. That implies a payment of some sort to ensure that a socially optimal level of resilience is maintained.

There are localised examples of this approach. Most notably in energy markets where capacity payments are made via auctions to suppliers, so they invest in enough electrical capacity to maintain reliability. There are various obvious difficulties in scaling up that approach to cover a number of industries and value chains at a global level. One is working out which value chains to target. It is fairly clear, but mainly with the benefit of hindsight, where the major bottlenecks are in the current crisis. But the nature, locations and impacts of future shocks are hard to project. There are also questions about where the funds would come from. One possibility is regional cooperation: countries can pool funds and establish facilities that could be activated in a crisis (perhaps along with compulsory licensing). The threat of exercising this option could in turn incentivise businesses in value chains to take resilience planning more seriously.

The challenge of resilience is therefore one on which the international trading system needs to work on urgently. The good news is that its underlying principles based on non-discrimination, transparency and replacement of quantitative measures by price-based measures, are the correct ones for dealing with the problem. That challenge is that it is these very principles that governments opportunistically reject as crisis looms, with deleterious results. To stop this from becoming recurring pattern, longer term resilience planning will require establishing a specific inter-governmental forum. That forum should be within the WTO, but will require cross-agency collaboration. It should focuses on resilience building measures, their payoffs, and their trade policy impacts. Obviously, no amount of institution-building will compensate for a basic absence of political will and a willingness to indulge in beggar-thy-neighbour policies and geopolitical power plays. The task for defenders of multilateralism is to remind politicians that it is these forces that have cost the world dearly in the past, and that indulging in them will create turmoil for the future.

[1] A useful resource on understanding the economics of Covid 19 and its implications for policy can be found in Joshua Gans (2020), Economics in the Age of Covid, MIT Press.