An interactive trade policy simulator for the UK

One of the objectives the UK has set for itself on leaving the European Union is to conclude Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with its major trade partners. The White Paper on future arrangements between the UK and the European Union (EU) proposes a free trade agreement (FTA) between both parties. It also sets specifically mentions the United States, Australia and New Zealand. The UK will also need to agree with partners with whom it has a FTA via the EU (such as Canada, Korea, Singapore, and Japan) that such FTAs will apply on a bilateral basis. The UK’s partners are also being active. In October, the United States Trade Representative announced that he would seek congressional authority to negotiate an agreement with the UK (along with the EU and Japan). The Japanese Prime Minister has said he would “spare no effort” in helping the UK acceded to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which includes Japan and 10 other nations, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Singapore.

How far the UK (and its partners) stand to gain from the FTAs – whether with the EU or the other partners – depends on their depth. As far as trade is concerned, by “depth” we mean the scope of disciplines that contained in the agreement on goods and services. In practice, the depth of FTAs varies. The EU is the deepest FTA currently in existence, through the application of its single market principles. Other FTAs, including ones struck by the EU with non-members, have tended to be shallower. In particular, they have limited effects of services trade liberalisation (over an beyond what partners offer to each other on a non-preferential basis) and have limited disciplines on regulation.

Interactive Model

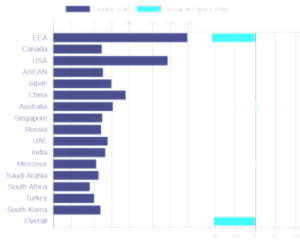

Use the slider controls to set your forecast for the post-brexit situation, or click on one of the preset scenarios as a starting point. The far left of the sliders represents "No Trade Deal", with the far right representing a "Deep Trade Deal". Mouseover/select the bars on the chart to show the forecast export figures or the change from the current. Mouseover/select areas on the world map below to see the split between goods and services.

The simulation tool we have prepared offers the possibility of measuring the effects on UK exports of good and services of different configurations of FTAs with the EU and with other trade partners. Users are allowed to select the depth of agreement in goods and in services between the UK and the trade partner in question. The tool offers three levels of depth:

- no FTA;

- a “vanilla” FTA that is consistent with the level of liberalisation seen between, say, the EU and non-EU members such as Canada; and

- A deep FTA that is equivalent to the level of liberalisation seen in the European Economic Area.

Users can set levels of each trade partner by using the sliders – moving left to right to increase depth.

They may also choose from a selection of pre-set scenarios, labelled as follows:

- “Doom and Gloom”:

- Hard exit from EU.

- Exit from all existing FTAs concluded by the EU (moving from vanilla to nothing for Canada, Japan, Singapore, South Africa, Turkey and Korea).

- Others unchanged

- Bearish: Exit from EU, UK negotiates a vanilla agreement in place (scenario 1) and exit from all EU negotiated FTAs (as above).

- Moderate: UK and EU negotiate a vanilla FTA, and the UK and manages to roll over all existing FTAs, and negotiates two new ones: Australia and Mercosur.

- Bullish: the UK secures a Deep FTA with the EEA, retaining current levels of integration in goods and services, and concludes vanilla FTAs with a series of partners: the US, ASEAN, China, Australia and Mercosur

- Sunny Uplands: the UK secures a deep FTA with the EEA, converts vanilla FTAs with other partners into deep ones, and negotiates new vanilla FTAs with Russia, India, the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

The trade effects are estimated by using coefficients mapping the depth of liberalisation to bilateral flows on the basis of a gravity model (see here for a further discussion of why such models are a necessary part of trade modelling).

The results are not intended to be predictive. Rather, they provide an illustration of how alternative policy scenarios can play out in relation to each other. In particular, a key variable to observe is the magnitude of losses arising from a departure from current deep arrangements between the UK and the EU, compared to gains arising from signing FTAs of varying depth with other partners.

One major caveat in interpreting the results is that while simulation can be “clean” exercise, negotiating and implementing FTAs are not. As observed in the case of a proposed FTA with the US, there are likely trade-offs between the depth of integration achieved with the EU, on one hand, and the depth of the FTA negotiated with the US on the other. The trade-off arises to a large extent because of the importance of regulation in affecting trade flows, and the divergence in approaches to regulation between the EU and the US. Achieving “regulatory alignment” with one may mean, for the UK, foregoing (to an extent at least) alignment with the other. In light of this, one way of interpreting the results from deep liberalisation scenarios with non-EU FTA partners is to treat these as upper bounds and compare them to the value of trade at risk with the EU.