Far out, down under: some lessons from Australia for UK trade policy post-Brexit

The political tumult in the UK over the manner in which Brexit would happen has all but drowned out discussions on the UK’s trade policy after Brexit. Admittedly, the matter of a UK-USA free trade agreement periodically resurfaces. But usually in headline-grabbing ways shorn of serious analysis, as was the case during US Vice President Pence’s visit. The idea of an “independent trade policy” was touted as one of the prizes of Brexit. As pointed out elsewhere, a number of challenges need to be tackled if that is to move from slogan to reality. One way of approaching these challenges is to consider lessons from other countries that embarked on ambitious reforms in response to domestic and external shocks. In this piece we look at the Australian reform experience over the last four decades. We argue that the positive lessons for the UK stem largely from Australia’s trade reforms in the 1980’s and 1990’s, a period of unilateral reform anchored in multilateral rules. Whereas insights from its more recent experiences in negotiating preferential free trade agreements are more in the way of cautionary tales.

Reforms the Australian way

Though Australian prospered in the post-war period, by the 1980’s politicians and policymakers had realised that the existing model, relying heavily on state intervention and protectionism, was responsible for a decline in relative living standards, and was not robust to external shocks. That realisation was in part driven by the loss of preferential market access to the UK after the latter joined what was then the European Economic Community.

Key initial steps in the reform process involved the floating of the exchange rate in 1983, and the relaxation of capital controls. Beginning in the late 1980s and continuing through the 1990s, the government also embarked on a progressive and comprehensive programme of tariff reductions across all sectors. WTO analysis shows that by 1998, over 85% of tariff lines had duties of between 0 and 5%, compared to 44% in 1993. Some sectors, such as automotives, saw much higher tariffs, and these would continue to be phased out over subsequent decades.

Three main features of the tariff reform process stand out. The first is that it was unilateral i.e. implemented without any explicit qui pro quo being asked of from trade partners. Policy makers, and more importantly politicians, had internalised the fundamental economic principle that when it comes to trade liberalisation, it is more blessed to give than to receive. Most notably, in his 1991 speech to parliament “Building a competitive Australia”, the then Prime Minister Bob Hawke argued that “the most powerful spur for greater competitiveness is further tariff reduction”. The proposals of the Hawke-Keating government drew heavily on the analyses provided by the then Industries Commission (later renamed the Productivity Commission), and prominent academics such as Ross Garnaut.

The second feature is that was that the unilateral reforms were anchored in a commitment to multilateral rules. Australia bound its tariff reductions in its commitments made through the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations (completed in 1994). The process of binding provided legal certainty and a safeguard against policy reversals. Australia also pushed for, and achieved, the inclusion of rules on agricultural trade under the Uruguay Round agreements.

The third feature is that the trade liberalisation programme was part of a wider programme for raising productivity in growth in Australia, that included micro-economic reform and reforms to competition policy. These reforms complemented trade reforms, in the sense that they were designed to boost economic efficiency and productivity. They also complemented traditional trade liberalisation because they opened the way for liberalising trade and investment in services sectors. This is because the keys to services trade liberalisation lie in the creating contestable markets by lowering barriers to entry, and by reforming regulation to make it more efficient and less likely to impose dead-weight costs.

From a trade perspective, the unilateral programme provided most of the heavy lifting for Australia’s trade performance. Trade to GDP rose from the 10-12% range in the later 1980s to around 20% at turn of millennium, and has remained there since. Exports grew at annual average of 6.3% between 1990 and 2004. They have grown at around 4.3% from 2004 onwards.

Preferential pitfalls?

The prevailing consensus on trade policy changed in Australia in the early 2000s. Long standing scepticism towards preferential free trade agreements (outside an agreement with New Zealand in 1983) was replaced by a growing enthusiasm for these arrangements. Eight bilateral FTA’s were signed and had entered into force by 2019, alongside two regional FTAs: a collective one including ASEAN countries and New Zealand, and the 11-country CPTPP[1]. Notable bilateral FTAs include ones with the United States (2005), Korea (2014), Japan (2015) and China (2015).

While the trade policy reforms in the 1980s and 1990s were seen as domestic reforms anchored in a wider programme of reforms driven by key economic ministries such as the Treasury, the enthusiasm for preferential arrangements was largely driven by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) in order to secure better market access overseas[2]. This partly reflected a return to a mercantilist mindset which viewed unfavourably the proposition that Australia should liberalise without “getting something in return”. It also reflected a view that the WTO had stalled as a negotiating forum, and that countries needed to find other ways of going beyond the WTO, particularly in areas such as services, investment, intellectual property, government procurement and regulation. There was also key political considerations, notably in the FTA with the United States and more recently with China.

Economists have been by and large sceptical of the payoffs from these preferential arrangements. The Productivity Commission reviewed Australia’s preferential agreements in 2010 and found that their impacts were at best modest. It also recommended that domestic reforms should not be delayed to gain “bargaining coin” in negotiations with partners.

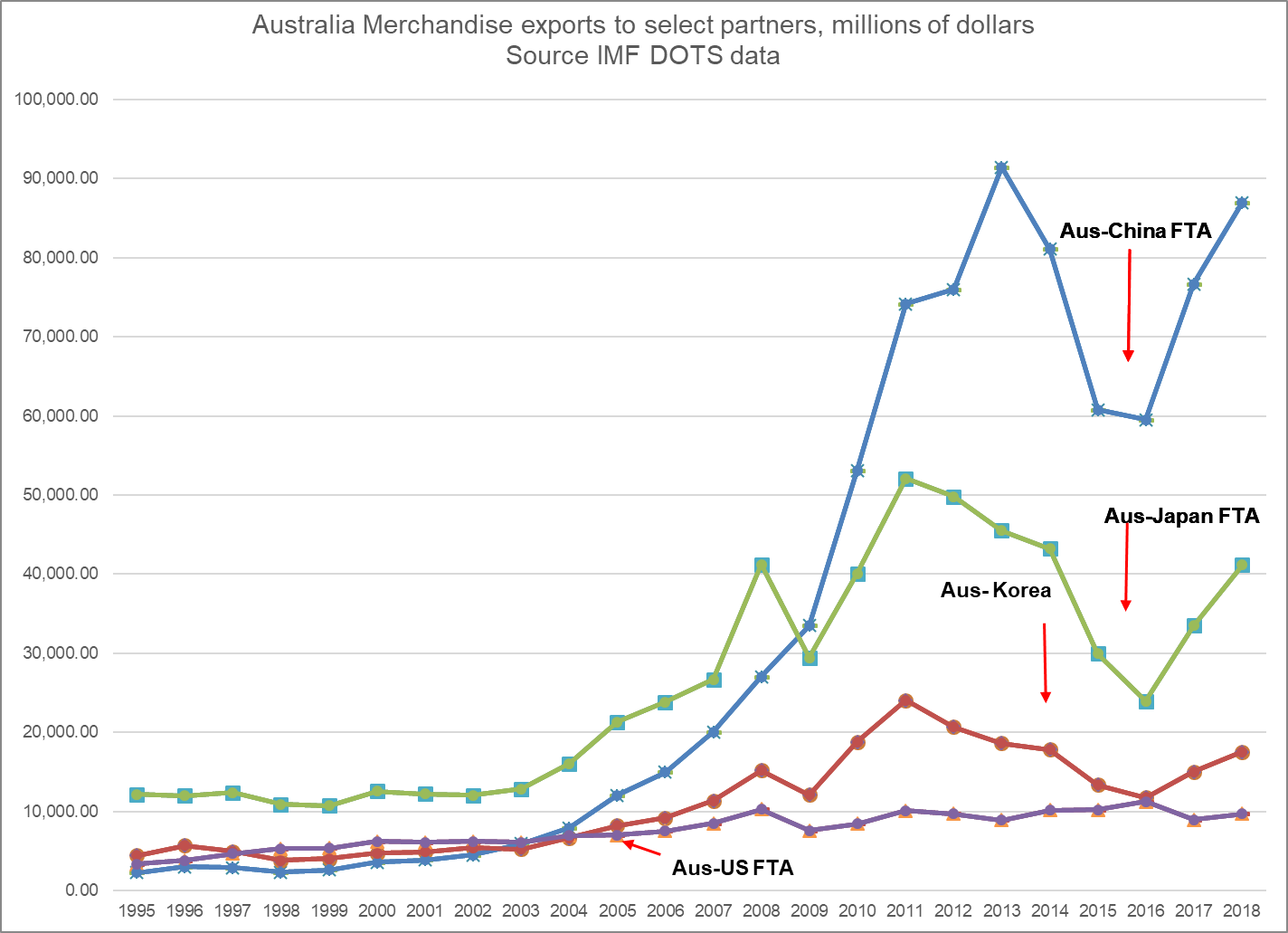

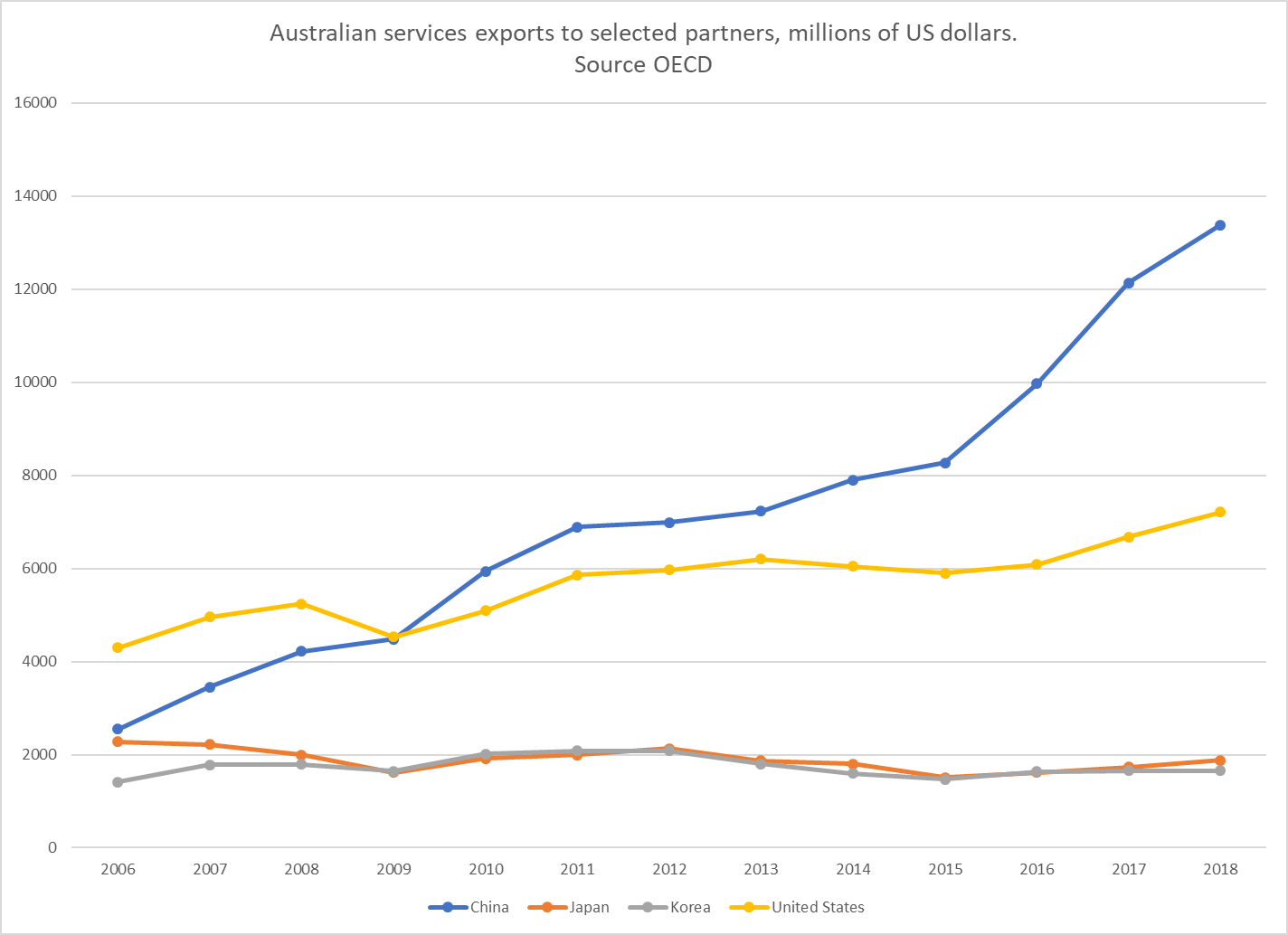

The Commission’s findings are relevant nearly a decade after their publication. Even focusing narrowly on export growth between Australia and its FTA partners (see Figures 1 and 2 below)[3], there is limited evidence of any change in export growth in either goods or services to these partners, or indeed any discernible pattern other than that reported export values are driven by the inherent vagaries of growth and demand in partner countries.

The one possible exception is the case of China. Services exports increased rapidly, mainly driven by education and travel services. The increase does not reflect the establishment of Australian education providers in China (in services trade speak., mode 3 supply) but rather the increased intake of Chinese students by institutions in Australia (in services speak, mode 2 supply). This increase may in part be attributable commitments made by Australia under the FTA to facilitate the entry of Chinese students., who then also had a clear pathway to residency. But these facilitating measures were part of more general (unilateral and non-preferential) reforms undertaken by Australia prior to the conclusion of the FTA with China. Other push and pull factors not connected to the FTA,, including GDP growth in China, are also likely contributing factors.[4] From a political economy point of view, the arrangements would have been satisfactory for China, which had an interest in promoting ease of entry to Australia, and for Australia, which had an interest in increasing its export potential in services.

One argument in support of Australia’s FTA strategy is that the purpose of the FTAs is not to secure additional liberalisation, but to provide increased security of access. This is especially true in services: commitments made at the WTO are dated and weak. In particular, levels of liberalisation committed to are a lot weaker than actual levels. Because it is the commitments that are binding, there is always a fear that actual liberalisation can be rolled back. FTA commitments are seen as a way of mitigating that possibility of roll back. While valid, it should be noted that this is not the argument usually put forward by politicians extoling the virtues of the agreements they signed.

Moreover, the strategy followed by Australian has had drawbacks too. One is the scope of demands placed by partners to a negotiation. In the case of the US-Australia FTA, the former asked that Australia’s mechanism for accessing medicines at low cost – the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme – be open for negotiation. Australia demurred. What could have been a sticking point was eventually resolved, partly because for political reasons the then American administration under George W. Bush wished to reward the Australian government, led by John Howard, with a FTA in recognition for Mr. Howard having committed troops to Iraq. The inclusion of demands for deep changes to regulation and public policy raises various challenges, not least because the welfare effects of changes are heavily contingent on their design and context. While “lower is better” is generally true for tariffs and border measures, the same cannot be said for regulation.

A second argument is that a more recent motivation for FTAs is the recognition that parties can set rules in new areas such as data and digital trade. If a large mass of participants join a FTA, this could create a first-mover advantage in a world of unbundled supply chains. This was one of the main motivations behind the CPTPP, and why it also excluded China. The approach raises the question whether it really is in the interest of smaller countries to promote the emergence of a global trade regime based on rivalry between large factional blocks. Lessons of history would suggest not.

The overall lesson from Australia stands: its free trade agreements have generally been weaker than the global average. Gains from FTAs have occurred where commitments in them have reflected a wider process of unilateral domestic reform. And preferential trade liberalisation is more a political construct than an economic one. Accordingly its benefits will be oversold by politicians who are incentivised to do so for political reasons, and under-equipped to understand the economics.

Lessons for the UK

The challenge for the UK is to find its place in global trade at a time when, as a result of Brexit, the UK is likely to erect at least some barriers to the flow of goods, services and labour with its largest trading partner (and quite possibly between its constituent parts depending on how negotiations on the Irish border issue play out).

Recent public and political discussions have framed the concept of an independent trade policy narrowly, in terms of bilateral preferential free trade agreements. The Australian experience points to the pitfalls of such an approach. Certainly, there is very little reason to believe that copying the Australian approach to FTAs can deliver anything like the boost in trade sought by the UK, and that it would make up for trade losses incurred by the UK in a moderate-to-hard Brexit.

What the Australian experience does point to is that Brexit could provide an opportunity for internal reform. Clearly, the UK in 2019 is already a highly liberalised economy. However, there are areas that appear ripe from reform, notably ones (such as agriculture and some manufacturing activities) where the UK would start off by inheriting the EU’s protectionism. In these sectors, the UK will need to develop a programme of reform that accommodates the social and distributional effects of liberalisation. It will do so at a time when political appetite for liberalisation is weak: it is hard to imagine any politician in the UK or indeed elsewhere in the industrial world giving a speech similar to that of Mr. Hawke in 1991. Moreover, whereas Mr. Hawke managed to craft a narrative of how domestic reforms could lead to an outward-oriented Australia, the dominant narrative so far behind Brexit has largely been inward-looking, with the leave vote crystalizing fears regarding immigration and nervousness about globalisation. It will be a challenge for the UK to replicate vene the more limited the reforms that Australia undertook in relation to overseas foreign students, and which were included in the China FTA package. It is clear that business favours a more liberal regime for students, and the question is how far political leadership may wish to go in following businesses (perhaps in an attempt to win them over to the idea of leaving the EU) and in the face of Breixter resistance.

Another lesson from Australia is that trade reform needs to be anchored in wider domestic reforms. In the UK, a long-standing challenge has been to increase productivity. While trade reforms can contribute to that, closer attention needs to be paid to the micro-determinants of productivity, notably at the firm level. This is especially true given that a large body of research suggests that it is the more productive firms that are able to take advantage of the openings created by trade liberalisation.

A final lesson is that trade policy reform relies on institutional reform. In Australia, the Productivity Commission (and prior to that the Industry Commission) played a key role in providing the analytical and intellectual rigour to guide and evaluate reforms. A similar body is required in the UK, particularly given the highly politicised nature of debates on trade in the UK, and the propensity to favour catchphrases such as “Global Britain” over principled thinking.

The main uncertainty in all of this is that whereas Australia helped to push forward, and benefited from, an unprecedented era of multilateral rule-making in international trade, the UK will be embarking on its Brexit venture precisely at a time at which the governance of world trade is unravelling at the seams. That this is the case is due to in part to the actions of the current US administration, but also because of the upswing in protectionism that has taken place over the last decade. Whether the UK, as a G7 nation, is able to set a clear vision for multilateralism, and rally sufficiently large numbers of partners to the cause, will prove critical to its post Brexit trade prospects.

[1] Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership, originally negotiated as the Trans Pacific Partnership including the USA, which withdrew from the partnership under the Trump administration.

[2] Malcolm Bosworth and Ray Trewin (2011), “Australian PTAs in services: Much ado about nothing”, NCCR Trade Regulation Working Paper, No 2011/ 152

[3] The measure is crude since even a significant increase in trade to a particular partner would need to take into account the potential for trade diversion from others.

[4] See notably Junfang Xi, Weihuan Zhou and Heng Wang “The impact of the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement on Australia’s education exports to China: A legal and economic assessment”, World Economy, September 2018.